Amebiasis Risk Assessment Tool

This tool estimates your risk of amebiasis based on travel history, water safety practices, and symptoms. It is for informational purposes only and should not replace professional medical advice.

Personal Risk Factors

Risk Assessment Result

Amebiasis has been popping up in headlines around the world, often tangled up with scary claims and half‑truths. If you’ve seen an alarming tweet, a sensational TV segment, or a misleading blog post, you might wonder what’s real and what’s just hype. This article cuts through the noise, explains how the disease really works, and debunks the most common myths that keep people up at night.

What is Amebiasis?

Amebiasis is a parasitic infection of the large intestine caused by the protozoan Entamoeba histolytica. It’s not a new disease-cases have been recorded for centuries-but modern travel and media exposure have revived public interest.

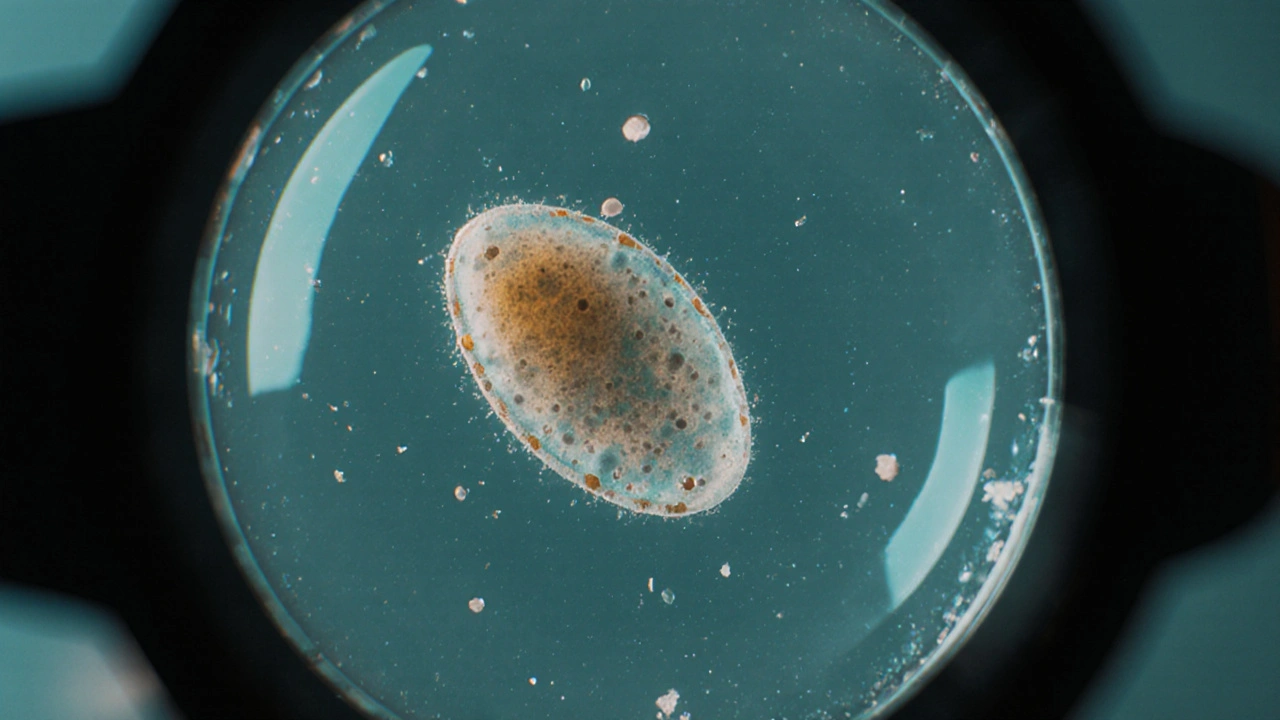

The Parasite Behind the Problem: Entamoeba histolytica

Entamoeba histolytica is a single‑celled organism that thrives in contaminated water or food and can invade the intestinal lining. When the parasite breaches the gut wall, it can cause bleeding, ulceration, and in severe cases, spread to the liver.

How People Get Infected

Transmission is simple but nasty: ingesting cysts from contaminated water, raw vegetables, or food handled by someone with poor hand hygiene. The risk spikes during travel to endemic regions (South‑East Asia, parts of Africa and Latin America) where water treatment is inconsistent. Even in high‑income cities, outbreaks can surface when communal water sources are compromised.

Key factors that raise infection odds include:

- Drinking untreated tap water or ice made from it.

- Eating salads or fruits washed with unsafe water.

- Close contact with an infected person who hasn’t completed treatment.

Symptoms: When Should You Be Concerned?

Diarrhea is the most common early sign, usually accompanied by abdominal cramps, fever, and occasional blood or mucus in the stool. Most infections are mild and resolve on their own, but about 10‑20% progress to dysentery or extra‑intestinal disease.

Red‑flag symptoms that demand medical attention include:

- Persistent bloody stools for more than three days.

- Severe abdominal pain or sudden weight loss.

- Fever above 38.5°C (101.3°F) with chills.

- Signs of liver involvement, such as right‑upper‑quadrant pain.

How Doctors Diagnose Amebiasis

The gold standard is a stool test that looks for cysts or trophozoites under a microscope. Modern labs often use antigen detection kits, which boost sensitivity.

When intestinal samples are inconclusive but suspicion remains high, serology can detect antibodies, especially useful for extra‑intestinal disease. Imaging (ultrasound or CT) helps identify liver abscesses, the most common complication outside the gut.

Treatment Options and What to Expect

Metronidazole is the first‑line drug, given for 7‑10 days to eradicate the active parasite. Because metronidazole doesn’t kill cysts, a second drug-often a luminal agent like paromomycin-is prescribed for a few days to prevent relapse.

The regimen typically results in rapid symptom relief within 48‑72hours. Side‑effects are usually mild (nausea, metallic taste) and resolve after treatment ends. For severe cases or liver abscesses, hospitalization and intravenous therapy may be required.

Myth‑Busting: What the Media Gets Wrong

| Myth | Fact |

|---|---|

| "Amebiasis is only a problem in third‑world countries." | Outbreaks have occurred in well‑developed cities when water supplies were contaminated. Travel brings the parasite to any region. |

| "If you have a stomach ache, you must have amebic dysentery." | Abdominal pain is nonspecific. Laboratory confirmation is needed before starting anti‑amoebic therapy. |

| "Antibiotics always cure amebiasis instantly." | Only specific anti‑amoebic drugs work. Broad‑spectrum antibiotics are ineffective and may mask symptoms. |

| "A single dose of medicine prevents future infection." | Treatment clears the current infection but does not provide immunity. Reinfection is possible if exposure recurs. |

| "The World Health Organization says amebiasis is no longer a threat." | WHO still monitors amebiasis as a neglected tropical disease, estimating 50‑60million cases worldwide each year. |

Understanding these distinctions helps you avoid panic and make informed health choices.

Public Health Perspective

World Health Organization (WHO) classifies amebiasis as a neglected tropical disease. Their surveillance data highlight that inadequate sanitation and unsafe drinking water are the main drivers. WHO recommends routine water quality testing, community education on hand hygiene, and rapid case reporting to limit spread.

In high‑income countries, public‑health labs keep an eye on imported cases. When clusters appear-often linked to a single restaurant or water source-authorities issue boil‑water advisories and conduct environmental sampling.

Practical Steps to Protect Yourself

Whether you’re traveling or staying home, these habits dramatically cut infection risk:

- Drink only bottled, boiled, or properly filtered water.

- Peel fruits yourself; avoid salads prepared with questionable water.

- Wash hands with soap and clean water after using the toilet and before handling food.

- If you develop diarrhea after a trip, seek medical care promptly-early stool testing speeds up treatment.

- Carry a small bottle of chlorine tablets or a portable UV purifier when you’re unsure about water safety.

Key Takeaways

- Amebiasis is caused by Entamoeba histolytica and spreads through contaminated water or food.

- Symptoms range from mild diarrhea to severe dysentery and liver abscesses.

- Accurate diagnosis relies on stool microscopy or antigen tests; never self‑diagnose.

- Standard treatment is metronidazole followed by a lumenal agent; most patients recover quickly.

- Common myths-such as the idea that only “third‑world” travelers get sick-are false; safe water practices protect everyone.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I get amebiasis from swimming in a pool?

Pool water is usually treated with chlorine, which kills the cysts of Entamoeba histolytica. Outbreaks are rare, but if a pool’s filtration system fails or the water is contaminated with sewage, infection is possible.

Do symptoms appear immediately after exposure?

The incubation period averages 2‑4 weeks, though it can be as short as a few days or as long as two months. This delay often confuses patients and clinicians.

Is a blood test reliable for diagnosing amebic liver abscess?

Serology is useful because antibodies appear early and remain detectable for months. However, a positive result alone doesn’t confirm an active liver abscess; imaging and clinical signs are needed for a definitive diagnosis.

Can I take metronidazole while pregnant?

Metronidazole is generally considered safe in the second and third trimesters, but doctors weigh the benefits against potential risks. If you’re pregnant, discuss alternative regimens with your obstetrician.

How long does it take to stop being contagious?

After completing the full course of metronidazole and the follow‑up lumenal agent, most patients are no longer shedding cysts within 48‑72hours. A repeat stool test can confirm clearance.

Comments

Mia Michaelsen

That myth about amebiasis being limited to “third‑world” nations is simply inaccurate; the parasite follows water, not borders, and outbreaks have been documented in affluent cities when municipal supplies were compromised. The life cycle of Entamoeba histolytica involves cysts that survive in contaminated water or food, so the key preventive measures are proper water treatment, hand hygiene, and safe food handling. Diagnosis relies on stool microscopy or antigen detection, not on vague “stomach ache” assumptions, and metronidazole followed by a luminal agent remains the standard regimen. In short, the facts are clear: you can get infected anywhere if proper precautions are ignored.

October 12, 2025 at 00:00

Kat Mudd

First, let me say that the media loves drama and you can see that in every headline about amebiasis because they want clicks and they don’t care about nuance. The parasite itself is tiny but it knows how to survive in the most unexpected places and that is why it shows up where we think we are safe. You read about a travel warning and suddenly you think every glass of tap water is a death sentence and that is a misinterpretation of risk. The real risk comes from drinking water that has not been boiled or filtered or from eating salads washed in questionable water and that is simple to avoid. When you travel you should carry a purification tablet or a portable UV purifier and that habit will make a huge difference. The symptoms can be mild at first like a bit of diarrhea and you might ignore them but if you notice blood or persistent cramps you should get tested right away. The stool test is not a myth it actually looks at the parasites under a microscope and modern antigen kits are even more sensitive. Treatment is short you take metronidazole for a week and then a second drug to clear cysts and most patients feel better within three days. People think antibiotics are a cure for everything but that is wrong in this case because broad‑spectrum antibiotics have no effect on the parasite. The WHO still tracks amebiasis as a neglected tropical disease and estimates tens of millions of cases each year so it is not a thing of the past. Prevention is about clean water hand washing and proper cooking practices and those are basics that apply everywhere. You do not need to live in a jungle to get sick you just need a contaminated bite of food or sip of water. The myth that only “third‑world” travelers get amebiasis is busted by cases that appear in high‑income countries when a municipal line is breached. The liver abscess complication is serious but rare and it shows why early diagnosis matters. So the bottom line is that sensible hygiene, safe water and prompt medical care are the real shields against this parasite.

October 12, 2025 at 01:00

Pradeep kumar

Great overview! From a clinical standpoint, the diagnostic algorithm often starts with a rapid antigen detection assay to increase sensitivity, followed by confirmatory microscopy if needed. In resource‑limited settings, stool concentration techniques can boost yield, and molecular PCR is emerging as a gold standard where available. Therapeutically, the metronidazole‑paromomycin sequence targets both trophozoites and cystic forms, ensuring eradication and minimizing relapse risk. Your emphasis on water treatment aligns with the One Health approach, integrating environmental, animal, and human health to curb transmission.

October 12, 2025 at 02:46

James Waltrip

Honestly, the whole “trust the official guidelines” narrative feels like a scripted distraction; they conveniently hide the fact that water treatment facilities are often infiltrated with micro‑chips that could theoretically alter cyst viability. If you look beyond the glossy public health brochures, you’ll see a pattern of selective reporting that shields big pharma’s monopoly on metronidazole. It’s not paranoia to question why the same 7‑day regimen is pushed worldwide without mention of alternative herbal protocols that have been used for centuries. The sleek language in the WHO pamphlet is meant to lull us into complacency while they keep the true epidemiological data under lock and key.

October 12, 2025 at 05:33

Chinwendu Managwu

Haha, that’s a classic conspiracy spin 😂 but honestly, the water works in Nigeria run on budget and still manage to keep most citizens safe, so maybe the “micro‑chip” story is a bit over the top. Still, we should keep an eye out for any hidden agendas! 🌍

October 12, 2025 at 06:33

Kevin Napier

Hey folks, just wanted to add a quick practical tip: if you’re heading to an area with questionable water, bring a small iodine tablet bottle and a simple straw filter – they’re cheap and work wonders. Also, make sure to wash your hands with soap for at least 20 seconds after any bathroom break; it’s the simplest thing that stops the parasite dead in its tracks. Lastly, if you notice any diarrhea after your trip, don’t wait – get a stool sample taken as soon as possible so treatment can start early.

October 12, 2025 at 08:20

Sherine Mary

Those are valid points, though it’s worth noting that iodine can degrade certain medications, so timing matters.

October 12, 2025 at 09:20

Monika Kosa

True, the interaction between iodine and drugs isn’t widely advertised, which makes you wonder why pharma doesn’t push a clearer guideline – maybe they profit from the confusion.

October 12, 2025 at 10:20

Gail Hooks

It’s fascinating how a single‑celled organism can teach us about resilience and the interconnectedness of our ecosystems 🌱. When we respect water as a shared resource, we honor both our health and the planet’s balance. Let’s keep sharing knowledge and empathy across borders. 😊

October 12, 2025 at 12:30

Derek Dodge

yeah im agree w/ you its truely humbnling to see how small things can have big impact

October 12, 2025 at 13:30

Write a comment