What Exactly Is Dementia?

Dementia isn’t one disease. It’s a group of conditions that slowly steal memory, thinking skills, and the ability to do everyday things. People often think of dementia as just forgetting names or where they put their keys. But true dementia is worse than that. It’s when someone can’t follow a conversation, manage their money, or remember how to get home from a place they’ve been to a hundred times. And it gets worse over time.

The most common type is Alzheimer’s disease - it makes up 60 to 80% of cases. But that still leaves a big chunk of dementia cases that aren’t Alzheimer’s. Three other types - vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia, and Lewy body dementia - are just as real, just as serious, and often mistaken for something else. Getting the right diagnosis isn’t just about labeling. It changes everything: what treatments work, what medications to avoid, and how families should care for their loved ones.

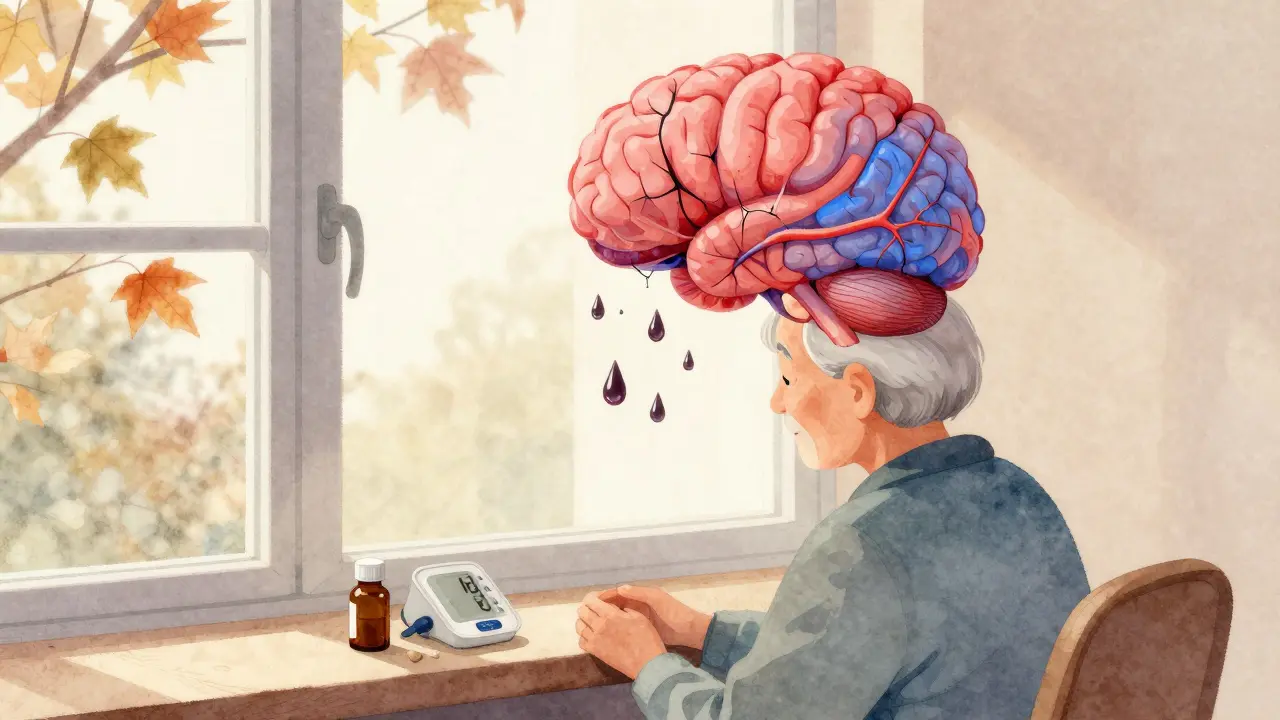

Vascular Dementia: When Blood Flow Fails

Vascular dementia happens when the brain doesn’t get enough blood. That’s usually because of blocked or burst blood vessels. High blood pressure, diabetes, and heart disease are the usual suspects. Over time, small strokes or long-term damage to blood vessels starve brain cells of oxygen. This isn’t one big event - it’s a series of small injuries that pile up.

What makes vascular dementia different is how it shows up. Symptoms don’t creep in slowly. They come in steps. One day, someone seems fine. The next, after a mini-stroke or TIA, they suddenly struggle to follow directions, forget recent events, or lose control of their bladder. They might also have trouble walking, lose balance, or feel weak on one side - signs you don’t usually see in early Alzheimer’s.

Brain scans show clear damage: white spots from tiny strokes, areas of dead tissue. The good news? You can slow it down. Controlling blood pressure (aiming for under 130/80), managing blood sugar, quitting smoking, and taking aspirin or similar drugs to thin the blood can cut the risk of more damage. The SPRINT-MIND trial showed that keeping systolic blood pressure under 120 reduced the chance of mild cognitive decline by nearly 20%. That’s not just prevention - it’s protection.

Frontotemporal Dementia: Personality Changes Before Memory Loss

If someone in their 50s starts acting completely out of character - becoming rude, impulsive, emotionally flat, or obsessed with food - don’t just assume it’s midlife crisis or depression. It could be frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Unlike Alzheimer’s, memory stays sharp in the early stages. Instead, the frontal and temporal lobes, the parts of the brain that control behavior, judgment, and language, start breaking down.

FTD is the most common form of dementia in people under 60. It hits hard and early. One person might stop caring about social rules, yell at strangers, or spend money recklessly. Another might lose the ability to speak clearly, struggling to find words or repeating the same phrase over and over. These aren’t choices. They’re symptoms of dying brain cells and abnormal proteins called tau and TDP-43 building up where they shouldn’t.

Diagnosis relies on brain imaging showing shrinkage in the front and sides of the brain. Neuropsychological tests focus on executive function - planning, organizing, decision-making - not memory recall. There’s no cure. But some antidepressants, especially SSRIs, can help with mood swings and compulsive behaviors. Speech therapy can support language loss. The big challenge? FTD is misdiagnosed as bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or depression in up to half the cases. That means people get the wrong meds, and families are left confused, thinking their loved one is ‘just being difficult’.

Lewy Body Dementia: Hallucinations, Fluctuations, and Hidden Parkinson’s

Lewy body dementia (LBD) is tricky. It’s got the memory problems of Alzheimer’s, the movement issues of Parkinson’s, and the weird hallucinations of something else entirely. It’s the third most common dementia, affecting about 1.4 million people in the U.S. alone. But it’s often missed - up to 75% of cases are first diagnosed as Alzheimer’s.

The key to spotting LBD is in the pattern. People don’t just forget things. Their attention wanders. One hour they’re alert and clear. The next, they’re staring into space, barely responsive. They see things that aren’t there - people in the room, animals on the floor. These hallucinations are usually visual, detailed, and often not frightening to the person experiencing them. They might also act out their dreams at night - yelling, kicking, punching - a condition called REM sleep behavior disorder.

And then there’s the movement. Muscle stiffness, slow steps, shuffling walk, reduced facial expression. These look like Parkinson’s. But here’s the critical detail: if dementia comes first or within a year of movement symptoms, it’s dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). If Parkinson’s comes first and dementia shows up years later, it’s Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD). Both are LBD.

What makes this dangerous? Standard Alzheimer’s drugs like donepezil can help with thinking, but antipsychotics - even mild ones - can cause severe reactions. Some people become rigid, stop moving, or even die from neuroleptic malignant syndrome. That’s why diagnosis matters so much. Dopamine transporter scans (DaTscans) can help confirm it. Cholinesterase inhibitors like rivastigmine are the preferred treatment. And families need to know: those hallucinations aren’t always signs of psychosis. Sometimes, they’re just part of the disease.

Why Getting the Right Diagnosis Changes Everything

Here’s the hard truth: if you treat vascular dementia like Alzheimer’s, you miss the chance to prevent more strokes. If you treat FTD like depression, you give someone pills that won’t help and delay real support. If you give an antipsychotic to someone with Lewy body dementia, you might put them in the hospital - or worse.

Each type needs a different approach:

- Vascular dementia → Focus on heart health: blood pressure, cholesterol, blood sugar. Prevent the next stroke.

- Frontotemporal dementia → Manage behavior with therapy and SSRIs. Support language loss with speech therapy. Avoid drugs meant for memory.

- Lewy body dementia → Use cholinesterase inhibitors. Avoid antipsychotics. Address sleep and movement issues. Educate caregivers about hallucinations.

Brain scans - MRI for vascular damage, PET scans for metabolic changes in FTD, DaTscans for LBD - are essential. Blood tests can rule out other causes like vitamin B12 deficiency or thyroid problems. But even with tools, diagnosis takes time. Many families wait years before getting a clear answer.

What Families Need to Know

Watching someone change because of dementia is heartbreaking. But understanding the type helps you prepare.

With vascular dementia, you can fight back - by helping them eat better, move more, take their meds, and avoid smoking. Every small step reduces the risk of another brain injury.

With FTD, you’re not dealing with memory loss. You’re dealing with a personality shift. The person might not recognize they’ve changed. You’ll need patience, boundaries, and help from specialists who understand behavioral neurology.

With Lewy body dementia, you’re managing a rollercoaster. Some days they’re sharp. Others, they’re lost. Hallucinations might seem scary, but they’re often not threatening. Sleep issues are real - securing the bedroom and using a mattress pad can prevent injuries. And never, ever give them antipsychotics without a neurologist’s approval.

Support groups for each type exist. The Lewy Body Dementia Association, the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration, and the American Heart Association all offer resources. Don’t go it alone.

The Bigger Picture: Underfunded, Overlooked

Alzheimer’s gets billions in research funding. Vascular, frontotemporal, and Lewy body dementia together get less than 5% of that. Yet they affect millions. We know how to slow vascular dementia. We’re starting to target the proteins in FTD and LBD. But without more money, progress stalls.

What’s clear? Dementia isn’t one enemy. It’s several. And treating them the same way is like using the same key for every lock - sometimes it works, but often, it breaks the lock.

If you or someone you love is showing signs of dementia - especially if memory isn’t the main issue - push for a specialist. A neurologist who works with dementia. Don’t settle for a quick diagnosis. Ask about brain scans. Ask about the type. Because knowing what you’re facing isn’t just information. It’s power.

Can vascular dementia be reversed?

No, brain damage from strokes or blocked vessels can’t be undone. But you can stop it from getting worse. Controlling blood pressure, diabetes, and cholesterol can prevent new damage. Many people stabilize for years with the right lifestyle and meds.

Is frontotemporal dementia inherited?

About 10 to 30% of FTD cases run in families, often due to mutations in genes like MAPT, GRN, or C9orf72. If multiple family members have early-onset dementia, behavioral changes, or ALS, genetic testing may be helpful. But most cases are not inherited.

Why are antipsychotics dangerous in Lewy body dementia?

People with LBD are extremely sensitive to antipsychotics because their brains have low dopamine levels and abnormal receptors. Even low doses of drugs like haloperidol or risperidone can cause severe stiffness, high fever, confusion, or even death from neuroleptic malignant syndrome. These drugs should be avoided unless absolutely necessary and only under strict neurologist supervision.

Can you have more than one type of dementia at once?

Yes. Mixed dementia - like Alzheimer’s plus vascular dementia - is common, especially in older adults. About 40% of Alzheimer’s patients also have Lewy bodies. This makes diagnosis harder but doesn’t change the need for careful, individualized care. Treatment focuses on the most disabling symptoms.

At what age does Lewy body dementia usually start?

Lewy body dementia typically begins after age 50, with most cases appearing between 60 and 80. It’s rare under 50. The average age of diagnosis is around 70, and life expectancy after diagnosis is usually 5 to 8 years, though some live longer with good care.

What to Do Next

If you’re worried about someone’s changes in thinking or behavior, start with a primary care doctor. But don’t stop there. Ask for a referral to a neurologist who specializes in dementia. Bring a list of symptoms - not just memory issues, but mood swings, hallucinations, sleep problems, or movement changes. Take someone with you. Write down questions.

Don’t wait for a crisis. Early diagnosis means better planning, safer meds, and more support. And if you’re already diagnosed, connect with a support group. You’re not alone. These conditions are complex, but with the right knowledge, families can make a real difference.

Comments

Joseph Cooksey

Let me tell you something nobody else will: vascular dementia isn’t just about strokes. It’s about the slow, silent erosion of autonomy. I watched my dad go from fixing his own car to needing help tying his shoes-all because his BP was never monitored properly. Doctors act like it’s just ‘aging,’ but it’s systemic neglect. That SPRINT-MIND trial? It’s not a suggestion-it’s a mandate. If you’re over 50 and your doc isn’t pushing for <120 systolic, find a new one. No, really. I’m not being dramatic. I’m just tired of watching people get ghosted by the healthcare system.

And don’t even get me started on how we treat FTD. People think ‘personality change’ means ‘they’re just being jerks.’ No. It’s neurodegeneration with a side of social stigma. My neighbor’s wife started shoplifting at 54. They called her ‘a liar.’ Turned out she had TDP-43 pathology. She didn’t want the money. She just couldn’t stop. That’s not moral failure. That’s biology screaming for help.

Lewy body? Oh yeah. I’ve seen the antipsychotic horror stories. My cousin’s husband got haloperidol for ‘psychosis’-he went rigid, stopped breathing, spent 11 days in ICU. They didn’t even do a DaTscan. Just assumed it was Alzheimer’s with ‘agitation.’ We lost three years. Three years of mismanagement because no one had the guts to say, ‘Wait, this doesn’t fit.’

We need to stop treating dementia like a monolith. It’s not one disease. It’s a constellation of failures-vascular, protein-based, neurotransmitter chaos. And we’re still using a hammer when we need a scalpel. The funding disparity? Criminal. Alzheimer’s gets billions. FTD gets crumbs. LBD gets hand-me-downs. We’re not just failing patients. We’re failing their families. And we’re doing it politely, with laminated pamphlets and corporate-sponsored webinars.

If you’re reading this and you’re a caregiver? You’re not alone. But you’re not being heard. Push harder. Demand scans. Demand specialists. Don’t take ‘we’ll monitor’ as an answer. You’re not being paranoid. You’re being proactive. And in this system? That’s the only kind of bravery left.

February 4, 2026 at 03:32

Sherman Lee

So… are we sure this isn’t all a Big Pharma ploy? 🤔

I mean, why do we suddenly need ‘DaTscans’ and ‘cholinesterase inhibitors’? Who profits? Who owns the labs? Who wrote the guidelines? I’m not saying it’s fake-but I’m saying: ask who benefits.

My uncle got diagnosed with ‘Lewy Body’ after 3 years of ‘Alzheimer’s.’ Then they switched meds. He got better. Then he died. Coincidence? Or just… another variable they don’t want you to see?

Also, why does ‘vascular’ always mean ‘control your BP’? What about air pollution? EMFs? 5G? We’re ignoring the real culprits.

Just saying. 🧠⚡

February 5, 2026 at 12:59

Lorena Druetta

I just want to say thank you for writing this with such clarity and compassion.

My mother was misdiagnosed with depression for two years before we found out she had frontotemporal dementia. The loneliness she felt-because everyone thought she was ‘choosing’ to be distant-was unbearable. When we finally got the right diagnosis, it didn’t fix her… but it finally let us love her the way she needed.

To anyone reading this: if someone you love is changing, don’t blame them. Don’t assume it’s ‘just attitude.’ Ask for a neurologist. Ask for an MRI. Ask for help. You’re not overreacting. You’re being a hero.

And if you’re a caregiver? You’re not a burden. You’re a light in the dark. Keep going. You’re doing better than you think.

February 5, 2026 at 14:17

Coy Huffman

man. i never realized how much of this is just… invisible. like, we talk about alzheimer’s like it’s the only one, but honestly? i think vascular might be the most preventable. like, if we just got people to drink water, walk more, and stop eating fried chicken, we could cut half the cases. but nope. we’d rather give out meds and call it science.

and ftd? dude. i had a coworker who turned into a completely different person. started yelling at clients, eating lunch with his hands, no shame. we thought he was drunk. turns out his frontal lobe was melting. he was 51.

and lbd? i had a neighbor who’d stare at the wall and say ‘the lady in the corner is singing.’ we thought he was crazy. turns out he was just… seeing things. and the doctors gave him antipsychotics. he stopped walking. i still think about that.

we need to stop treating dementia like a mystery and start treating it like a warning sign. your body’s yelling. are you listening?

February 7, 2026 at 07:02

Kunal Kaushik

My uncle had Lewy body. He’d wake up screaming because he saw ‘demons’ under the bed. We thought he was haunted. Turned out, it was the disease. We got him on rivastigmine and his nights got calmer. Not cured. But better.

Also, no antipsychotics. Ever. I’ll say it again: no antipsychotics.

February 7, 2026 at 12:34

Nathan King

While the article presents a clinically accurate overview, it lacks critical context regarding socioeconomic determinants of dementia presentation. The emphasis on pharmacological interventions and diagnostic imaging presupposes access to tertiary care, which is not universally available even within the United States. Furthermore, the framing of ‘stopping strokes’ as a sufficient intervention ignores the structural failures in primary care infrastructure that allow hypertension to go unmanaged in marginalized populations. A more robust analysis would integrate public health policy, insurance disparity, and racialized outcomes in dementia diagnosis. As currently framed, this discourse risks reinforcing a technocratic model of care that alienates those who need it most.

February 8, 2026 at 01:11

Wendy Lamb

One sentence: If you see someone acting weird, don’t judge-get them checked.

February 9, 2026 at 12:46

Antwonette Robinson

Oh, so now dementia has ‘types’? How convenient. Next you’ll tell me depression has subtypes based on which Netflix show you binge. ‘Oh, it’s not just sadness-it’s FTD with TDP-43!’ Sure. Tell that to the guy who just forgot his wife’s name because he’s 72 and tired.

My grandma had ‘Alzheimer’s.’ She forgot where the bathroom was. They gave her a $2000 scan. She died two months later. You think a DaTscan would’ve changed that? Or are we just selling fear to sell MRIs?

February 10, 2026 at 13:44

Ed Mackey

i just want to say… i read this whole thing. i’m not a doctor. i’m just someone whose mom got diagnosed last year. i didn’t know any of this. i thought she was ‘just forgetful.’

thank you. really. i’m going to take this to her neurologist next week. i’m gonna ask about blood pressure. i’m gonna ask about scans. i’m gonna ask if we’re treating the right thing.

even if i mess up the words… i’m gonna try.

February 11, 2026 at 18:45

Katherine Urbahn

It is imperative that we recognize the ethical and epistemological implications of pathologizing normal aging under the guise of ‘dementia.’ The proliferation of diagnostic categories-vascular, frontotemporal, Lewy body-is not merely clinical; it is ideological. It medicalizes natural cognitive decline, thereby expanding pharmaceutical markets and institutional control. The call for ‘brain scans’ and ‘specialists’ is not a humanitarian plea-it is a gatekeeping mechanism. Who decides what constitutes ‘normal’ cognition? Who profits? And why are we so eager to label our elders as ‘diseased’ rather than honored as the living archives of our collective memory?

Let us not confuse complexity with necessity. Let us not confuse intervention with compassion. Let us remember: dementia is not a diagnosis. It is a social construct dressed in neurology.

February 12, 2026 at 22:55

Alex LaVey

I’ve been volunteering at a memory care home for five years. I’ve met people with all three types. And you know what? They’re still people. The woman with FTD who hugs strangers? She’s not rude-she’s lonely. The man with LBD who sees butterflies on the ceiling? He’s not hallucinating-he’s telling us about his world. The guy with vascular dementia who can’t walk? He still laughs when you play his old country songs.

We don’t need more scans. We need more presence. More patience. More people who show up, even when they don’t understand.

You don’t have to be a neurologist to make a difference. You just have to care enough to sit beside them. Even if they forget your name. Even if they stare at the wall. Even if they don’t say a word.

That’s the real treatment. Not the pills. Not the scans. The presence.

February 13, 2026 at 11:25

caroline hernandez

From a clinical standpoint, the article accurately delineates the phenotypic profiles, but it underemphasizes the role of biomarker validation in differential diagnosis. For instance, CSF tau:p-tau ratios are now validated for FTD subtypes, and amyloid PET imaging can rule out Alzheimer’s co-pathology in LBD cases. The reliance on DaTscans for LBD is appropriate, but in resource-limited settings, clinical criteria (MDS 2017) remain robust. Also, note that SSRIs in FTD are most effective for disinhibition when dosed above 20mg/day-many clinicians underdose. And for vascular dementia: the 2023 AHA/ASA guidelines now recommend SGLT2 inhibitors for patients with diabetes and cognitive decline-not just statins. This is critical.

Also: mixed dementia is more prevalent than previously thought. Up to 60% of ‘Alzheimer’s’ cases have vascular co-pathology. This changes therapeutic strategy. If you’re treating for amyloid but not managing endothelial dysfunction, you’re leaving 40% of the pathology untreated. We need integrated protocols-not siloed categories.

February 14, 2026 at 11:32

Jhoantan Moreira

I’m from the UK and we’ve got a similar problem here. NHS waits for brain scans are 18+ months. People get misdiagnosed. Families burn out. We need better access. Not more jargon. More time. More staff.

Also, can we just agree that ‘dementia’ isn’t a death sentence? My mum had LBD. She still made me tea. She still laughed. She still knew my voice. That matters more than any scan.

Thanks for writing this. I’m sharing it with my local support group.

February 15, 2026 at 17:15

Amit Jain

I work in a clinic in India. We don’t have DaTscans. We don’t have PET. But we have eyes. We have families. We have time.

We look for steps in decline-sudden bladder control loss? Vascular.

We look for personality changes before memory loss? FTD.

We look for hallucinations + shaking + day-to-day confusion? LBD.

We don’t need fancy machines. We need trained nurses. We need community education. We need to stop treating this like a Western problem.

It’s a human problem. And we can help-even here.

February 16, 2026 at 01:23

Demetria Morris

I’ve been saying this for years. People with dementia aren’t ‘losing’ themselves. They’re becoming something else. Something quieter. Something more honest.

My mother stopped lying after her diagnosis. She stopped pretending. She stopped trying to be ‘normal.’

She started telling me what she really thought. About my husband. About my job. About how much she hated the nursing home.

It was brutal. But also… beautiful.

Maybe dementia doesn’t take away who we are.

Maybe it just strips away the masks.

February 17, 2026 at 00:33

Write a comment