When you take a pill on an empty stomach versus right after eating, your body doesn’t just digest it differently-it absorbs it differently. That’s not a myth. It’s science. And it’s why fasted vs fed state testing isn’t just a lab curiosity-it’s a requirement for safe, effective medications and a critical factor in how your body responds to exercise, nutrition, and metabolism.

What Fasted and Fed States Actually Mean

Fasted state means you haven’t eaten for at least 8 to 12 hours. No food. No sugary drinks. Just water. Your body’s switched to burning stored fat for energy. Blood sugar is low. Insulin is minimal. Digestive activity is quiet.

Fed state means you’ve eaten a meal-usually a standardized one-within the last 2 to 4 hours. Your stomach is full. Digestive enzymes are active. Blood sugar and insulin are up. The pH in your stomach drops. Gastric emptying slows down dramatically.

These aren’t just labels. They’re two completely different physiological environments. And the difference isn’t subtle. In fed state, gastric residence time jumps from under 14 minutes to over 78 minutes. Stomach pH can dip as low as 1.5, compared to 2.5 in fasted state. These changes directly impact how drugs dissolve, how quickly they move through your gut, and how much actually gets into your bloodstream.

Why Drug Companies Must Test Both

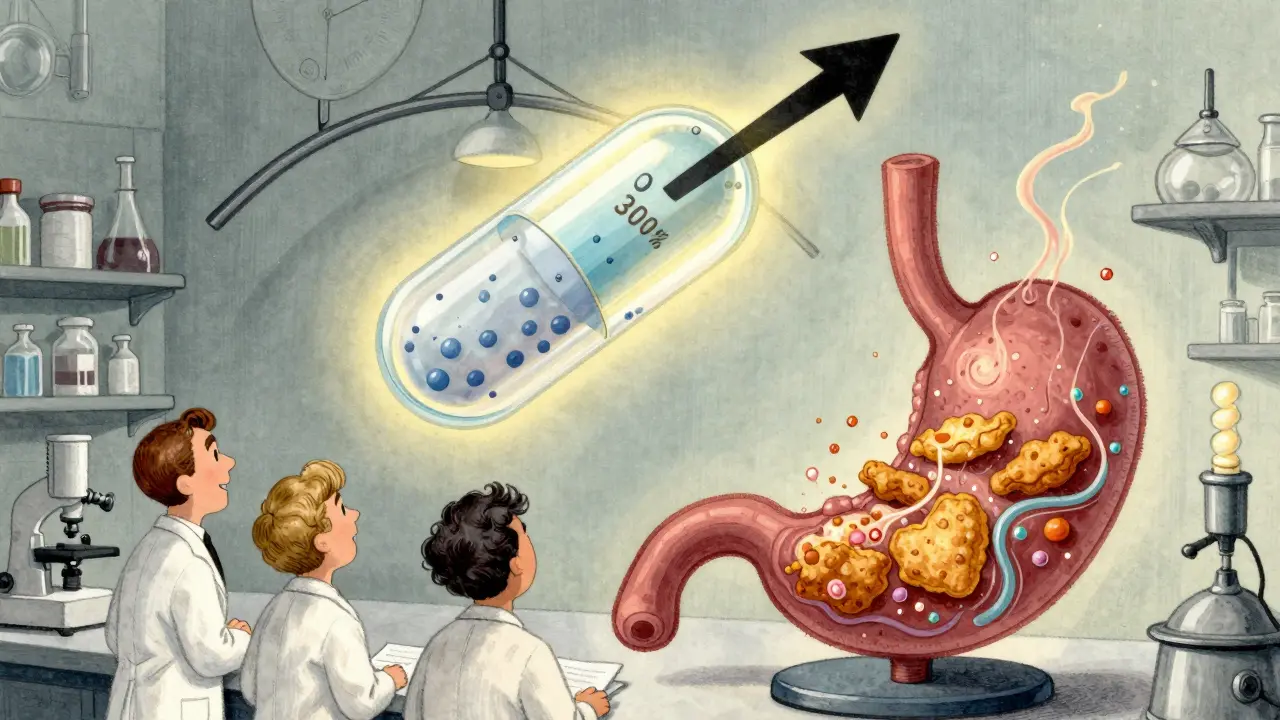

In the 1990s, the FDA realized something alarming: many drugs behaved unpredictably when taken with food. Some became more effective. Others became dangerous. One drug, fenofibrate, sees its absorption spike by 200-300% when taken with a high-fat meal. Another, griseofulvin, loses over half its effectiveness.

That’s why today, fasted vs fed state testing is mandatory for nearly every new oral drug application. The FDA requires companies to test their drugs under both conditions. The meal used in fed-state trials isn’t a snack-it’s a controlled, high-fat, high-calorie meal: 800-1,000 calories, with 500-600 of them coming from fat. It’s designed to mimic the worst-case scenario for absorption changes.

Why? Because if a drug’s absorption changes by more than 20% because of food, regulators can’t guarantee consistent dosing. For drugs with narrow therapeutic windows-like blood thinners, seizure meds, or chemotherapy agents-that’s a safety risk. A patient taking the same pill at breakfast versus dinner could get too much or too little. That’s why the European Medicines Agency now requires fed-state testing for all oral drugs where food effects are unknown. About 35% of drugs show clinically significant food interactions, according to a 2019 analysis of 1,200 applications.

How Food Changes Your Body’s Response to Exercise

This isn’t just about pills. It’s also about your workout.

When you train fasted-say, first thing in the morning before breakfast-your body relies more on fat for fuel. Free fatty acids in your blood rise by 30-50%. Your muscles turn on genes like PGC-1α, which boosts mitochondrial growth. That’s why some people swear by fasted cardio for fat loss.

But here’s the catch: you can’t go all-out. High-intensity efforts-sprints, heavy lifting, HIIT-drop by 12-15% in fasted state. Your muscles need glycogen. And without recent carbs, you’re running on empty. A 2018 meta-analysis of 46 studies found fed-state exercise improves endurance performance by 8.3% over longer sessions. But for workouts under 60 minutes? No real difference.

And here’s where it gets personal. Some athletes, like ultramarathoner Scott Jurek, train fed to sustain energy. Others, like CrossFit champion Rich Froning, train fasted to sharpen fat-burning efficiency. Both are right-for their goals.

The American College of Sports Medicine says fed-state training is better for competitive athletes. But for sedentary people looking to improve insulin sensitivity, fasted training shows 5-7% greater gains. Yet a 2021 study found no difference in body composition after six weeks of either approach. So what’s the real benefit? It’s not about burning more fat during the workout. It’s about how your body adapts over time.

The Hidden Problem: One Size Doesn’t Fit All

Here’s the twist: not everyone responds the same way.

Asian populations, for example, empty their stomachs 18-22% slower than Caucasians in fed state. That means a drug that works fine for one group might be ineffective-or too strong-for another. That’s why the FDA’s 2023 draft guidance now demands fed-state testing across diverse ethnic groups.

Even within the same person, genetics play a role. A 2022 study found that variations in the PPARGC1A gene explain 33% of how someone responds to fasted versus fed training. Some people thrive fasted. Others feel dizzy, weak, or nauseous. A 2022 Reddit survey of 1,247 fitness enthusiasts showed 68% performed better fed. But 42% of keto-focused users preferred fasted-though 31% admitted to dizziness.

That’s why blanket advice like “always train fasted” or “never take pills on an empty stomach” is misleading. The answer depends on your body, your goal, and your medication.

How to Get Accurate Results-Whether You’re Testing a Drug or Yourself

If you’re participating in a clinical trial, protocols are strict: sleep 7+ hours, avoid alcohol and caffeine for 24 hours, stay hydrated (urine specific gravity under 1.020), and don’t exercise before the test. The meal? Exactly 800-1,000 calories, 500-600 from fat, within 10% of the specified macronutrients.

If you’re experimenting with your own training? Control what you can. Test both states under similar conditions: same time of day, same sleep, same hydration. Don’t compare a fasted 6 a.m. run to a fed 7 p.m. bike ride. That’s noise, not data.

And if you’re taking medication? Always follow the label. If it says “take on an empty stomach,” wait two hours after eating. If it says “take with food,” don’t skip the meal. The difference isn’t just about absorption-it’s about safety.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters Long-Term

The global market for bioequivalence testing hit $2.7 billion in 2022. The sports nutrition industry, fueled by fed-state performance products, is projected to grow at 27% annually through 2030. Why? Because we’re moving beyond one-size-fits-all health advice.

Pharmaceutical companies now use continuous glucose monitors during fed-state trials to track real-time metabolic responses. Exercise scientists are testing genetic markers to predict who benefits from fasted training. This isn’t just science-it’s precision medicine.

What’s clear is this: fasted and fed states aren’t opposites. They’re tools. One isn’t better. Each reveals something different about how your body works. Ignoring one means you’re missing half the picture.

Whether you’re a patient, an athlete, or someone managing a chronic condition, understanding these two states helps you make smarter choices. It’s not about following trends. It’s about knowing how your body truly responds.

Is it better to take medication fasted or fed?

It depends on the drug. Some medications, like fenofibrate, absorb much better with food-sometimes 200-300% more. Others, like griseofulvin, absorb less. The label tells you why. If it says "take on an empty stomach," food can block absorption. If it says "take with food," the meal helps your body process it. Never guess-follow the instructions.

Does fasted exercise burn more fat?

Yes, during the workout, your body uses more fat for fuel in a fasted state-free fatty acids rise by 30-50%. But that doesn’t mean you lose more body fat over time. Studies show no difference in long-term fat loss between fasted and fed training. The real benefit of fasted exercise is metabolic adaptation: your muscles get better at burning fat. But you’ll hit a wall during high-intensity efforts. It’s a trade-off.

Why do drug trials use such a high-fat meal?

They use a high-fat, high-calorie meal (800-1,000 calories, mostly fat) to create the worst-case scenario for absorption. If a drug works fine under those tough conditions, it’ll likely work under normal meals too. This ensures the dosage is safe and effective no matter how people eat in real life.

Can I train fasted every day?

You can, but you shouldn’t. Fasted training reduces high-intensity performance by 12-15%. If you’re doing strength training, sprints, or HIIT, you’ll recover slower and train less effectively. It’s best used strategically-maybe 2-3 times a week for endurance or fat adaptation. Save fed training for your hardest sessions.

Are there risks to fasted training?

Yes. Some people feel dizzy, nauseous, or weak. Others report reduced workout intensity. In rare cases, especially with diabetes or low blood pressure, fasted training can cause dangerous drops in blood sugar. If you feel lightheaded, stop. Hydrate. Eat. It’s not worth pushing through.

How do I know if my medication is affected by food?

Check the prescribing information. Look for phrases like "take on an empty stomach," "take with food," or "food may affect absorption." If you’re unsure, ask your pharmacist. They have access to detailed data on how each drug interacts with food. Never assume-small changes in absorption can make big differences in safety.

Comments

Jerry Peterson

Really appreciate this breakdown. I used to take my blood pressure med on an empty stomach because the bottle said so, but I’d get nauseous every time. Switched to taking it with a light snack and boom-no more stomach issues. Turns out, my body just doesn’t like the shock. Always thought it was me being weak. Turns out, it’s science.

December 21, 2025 at 17:19

Ben Warren

It is, regrettably, a lamentable state of affairs that the general populace continues to conflate anecdotal experience with empirical evidence. The pharmacokinetic variance between fasted and fed states is not merely a nuance-it is a fundamental pillar of bioequivalence assessment. To dismiss the necessity of standardized fed-state trials is to invite therapeutic failure, and worse, iatrogenic harm. The FDA’s protocols exist precisely because laypersons, lacking training in clinical pharmacology, presume their subjective experience to be universally applicable. This is not merely ignorance-it is dangerous.

December 21, 2025 at 23:59

Sandy Crux

...And yet, nobody ever mentions that the "high-fat meal" used in trials is a grotesque, industrialized monstrosity-200g of fat? That’s not food, that’s a pharmaceutical torture device. Real people don’t eat like that. You’re testing absorption under artificial, extreme conditions, then applying it to normal meals... which, by the way, are rarely 800 calories of pure lard. This whole system is built on a strawman.

December 22, 2025 at 06:02

Hannah Taylor

lol the fda is just trying to sell more drugs. they made up the "fed state" thing so they can make you take pills 3x a day instead of once. also, your "standardized meal"? it’s the same crap they feed prisoners. why would you trust a system that feeds people that? they just want you dependent.

December 23, 2025 at 18:42

Theo Newbold

That 35% figure for clinically significant food interactions? It’s outdated. A 2023 meta-analysis in J Clin Pharmacol showed 41% of drugs have food effects that alter AUC by >25%. And that’s only the ones they bother to test. Most generics never get re-evaluated. You’re probably on one right now.

December 24, 2025 at 16:48

Jay lawch

Western medicine is built on lies. You think your body needs to be tested with a high-fat meal? In India, we’ve been taking medicine with chapati and dal for centuries. No one dies. No one gets sick. But Western labs? They need to invent problems to sell solutions. This fed-state nonsense is just another way to profit from confusion. Your body knows better than your pill bottle. Trust tradition, not corporate labs.

December 26, 2025 at 00:17

Cara C

I used to do fasted workouts religiously until I started feeling like I was running on fumes by mid-afternoon. Switched to a banana before training and my strength jumped. Not because I "burned more fat," but because I could actually push harder. The key isn’t fasted vs fed-it’s listening to your body. If you feel awful, change it. No one’s winning at being miserable.

December 26, 2025 at 22:21

Michael Ochieng

Just had a coffee with a clinical pharmacologist from Merck last week. She said something that stuck: "We test fed state not because people eat big meals, but because people eat inconsistently." One person has toast, another has a greasy burger, another skips breakfast entirely. The drug has to work across that chaos. It’s not about the meal-it’s about the variability of real life.

December 28, 2025 at 16:49

Dan Adkins

It is a matter of grave concern that the general public has been conditioned to treat pharmaceutical instructions as mere suggestions. The integrity of therapeutic outcomes hinges upon strict adherence to dosing protocols, whether in fasted or fed states. To deviate is not a personal choice-it is a public health risk. The data is unequivocal. The consequences are not theoretical. Compliance is not optional. It is a moral and scientific imperative.

December 30, 2025 at 14:25

Write a comment