When a brand-name drug’s patent expires, you’d expect cheaper generic versions to hit the market quickly. But in reality, many generics face legal roadblocks that delay their arrival for years-even after the original patent runs out. This isn’t random. It’s a system built into U.S. drug law, and it’s costing patients billions.

How the Hatch-Waxman Act Created a Legal Battleground

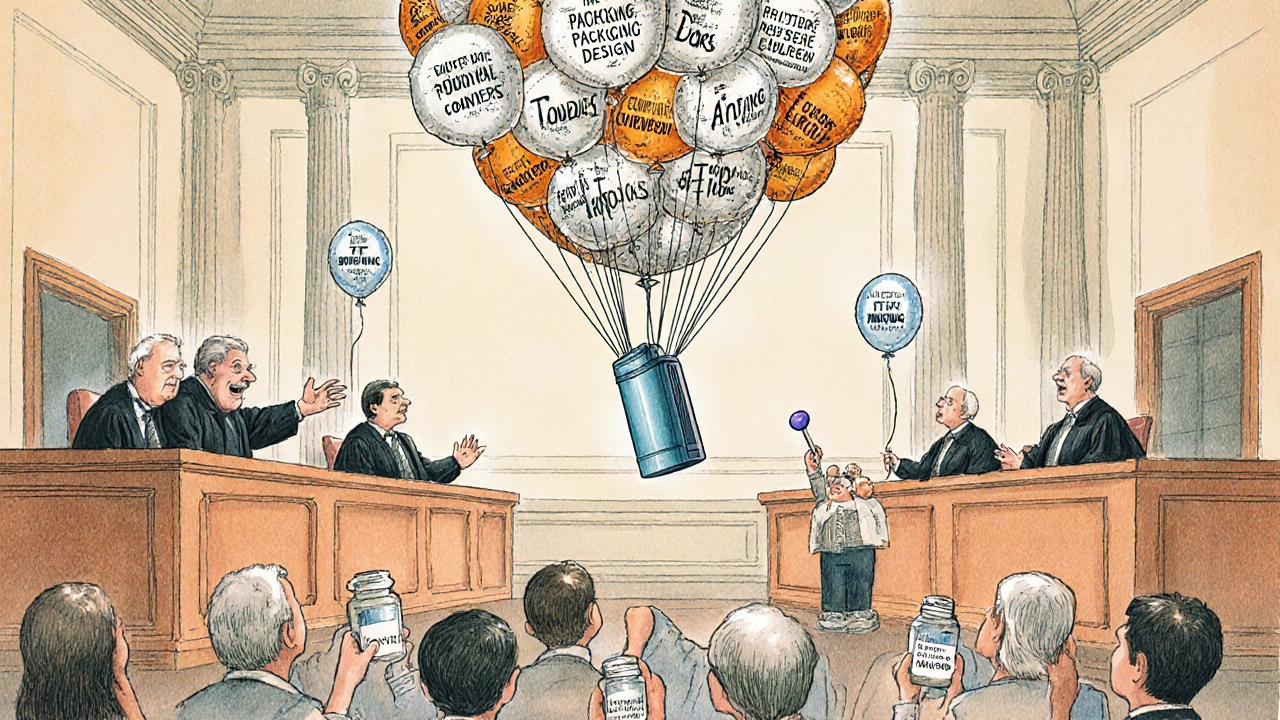

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, was meant to balance two goals: rewarding innovation and speeding up access to affordable drugs. It gave generic manufacturers a clear path to approval through Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs). But it also gave brand-name companies a powerful tool: the ability to sue when a generic company challenges their patents. Here’s how it works. Generic companies file an ANDA and include a Paragraph IV certification, saying they believe the brand’s patent is invalid or won’t be infringed. That’s a direct challenge. The brand company then has 45 days to sue. If they do, the FDA can’t approve the generic for up to 30 months. That’s not a review delay-it’s a legal freeze. This 30-month stay was designed to give courts time to resolve disputes. But in practice, it’s become a strategic pause button. Some brand companies have used it to delay generic entry for over a decade, even when the core patent has expired.The Orange Book: A List That’s Being Abused

The FDA’s Orange Book is supposed to be a transparent list of patents tied to brand-name drugs. Only patents covering the active ingredient, formulation, method of use, or manufacturing process should be listed. But that’s not always what happens. In 2025, a federal judge in New Jersey ruled that six patents listed for ProAir® HFA-an asthma inhaler-were improperly included. The patents covered the dose counter on the inhaler, not the drug itself (albuterol sulfate). Judge Chesler made it clear: “The drug for which Teva submitted its application was albuterol sulfate inhalation aerosol.” Patents on the device don’t count. That ruling is a big deal. Skadden’s September 2025 analysis estimates that 15-20% of all Orange Book listings could be invalid under this standard. Yet brand companies keep listing patents on packaging, delivery devices, and even software used with the drug. These aren’t protecting the medicine-they’re protecting profits. The Association for Accessible Medicines (AAM) found that brand companies often use this tactic to launch a series of lawsuits-each with a new patent, each triggering a new 30-month stay. One drug saw generic entry delayed by nearly 10 years because of this serial litigation strategy.Where Lawsuits Are Fought: The Eastern District of Texas

Not all courts are created equal when it comes to patent cases. In 2024, the Eastern District of Texas became the most active venue for pharmaceutical patent litigation, handling 38% of all cases. That’s up from just 12% a decade ago. Why? Because it’s known for being favorable to patent holders. Judges there have deep experience with complex pharmaceutical cases. The procedures are predictable. And the jury pool is seen as more likely to side with innovators. That’s why companies like Teva, Amgen, and Pfizer file their lawsuits there. The Western District of Texas and District of Delaware are also popular, but Texas now leads by a wide margin. This isn’t about where the companies are based-it’s about choosing the court that gives you the best shot at winning. Critics call this forum shopping. Supporters say it’s just smart legal strategy. Either way, it’s reshaping how these cases play out.

Pay-for-Delay: Settlements That Aren’t What They Seem

Sometimes, instead of fighting in court, brand and generic companies settle. On paper, it looks like a win-win: the brand avoids a risky trial, and the generic gets paid to stay off the market. But here’s the catch: those payments often come with a condition-don’t launch until the patent expires, even if you’ve already won your case. That’s called a “pay-for-delay” settlement. The FTC has spent years trying to stop it, calling it anti-competitive. Yet the IQVIA Institute found something surprising: on average, these settlements actually brought generics to market more than five years before patent expiration. That’s because without the settlement, many generic companies wouldn’t file ANDAs at all. The risk of losing a multi-million-dollar lawsuit is too high. John T. O’Donnell, an industry analyst, put it bluntly: “If you limit a generic drug manufacturer’s ability to settle cases, that manufacturer does not settle fewer cases-it submits fewer Paragraph IV ANDAs.” So the real issue isn’t just the settlements. It’s the entire system that forces generics to choose between a risky legal battle or a quiet exit.Patent Thickets: When One Drug Has 150 Patents

Some drugs are protected by dozens-even hundreds-of patents. Eliquis (apixaban) has 67. Semaglutide products (Ozempic, Wegovy, Rybelsus) have 152. Oncology drugs average 237. This isn’t innovation. It’s a legal wall. Each patent extends the clock. Each one can be used to trigger another 30-month stay. Even if one patent is invalidated, another one is ready to take its place. Dr. Rachel Sachs, a law professor at Washington University, calls this a “patent thicket.” And it’s getting worse. The average number of patents per drug has risen from 37 for small molecule drugs to 78 for biologics and biosimilars. The result? The average time from brand drug approval to first generic entry has doubled-from 14 months in 2005 to 28 months in 2024. For cancer drugs, it’s now an average of 5.7 years after patent expiration before generics appear.

Who’s Paying the Price?

All of this has a cost-and it’s not just paid by drug companies. The FTC estimates that improper Orange Book listings delay generic competition for about 1,000 drugs every year. That costs the U.S. healthcare system $13.9 billion annually. Patients pay more. Insurers pay more. Medicare and Medicaid pay more. Meanwhile, specialized law firms are thriving. Fish & Richardson, Quinn Emanuel, and Jones Day reported 35-40% revenue growth in patent litigation in 2024. The legal industry is profiting from the delay. The FDA is finally responding. In early 2026, new regulations will require brand companies to certify under penalty of perjury that every patent they list in the Orange Book meets legal standards. That’s a step forward. But it’s reactive. The damage has already been done.What’s Changing? And What’s Not

Generic manufacturers are fighting back with new tools. Inter partes review (IPR) at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) has grown by 47% since 2023. IPR lets challengers attack patents without going to court. But in April 2025, the Supreme Court’s decision in Smith & Nephew v. Arthrex made it harder for generic companies to file these challenges by tightening standing rules. The FTC has been aggressive too. In 2024, they challenged over 300 improper Orange Book listings. In May 2025, they sent warning letters to 200 more patents across 17 brand-name drugs, including major companies like Teva and Amgen. But the system still favors the status quo. The 30-month stay remains. The Orange Book is still full of questionable patents. The courts still hear hundreds of cases every year. The real change won’t come from lawsuits or letters. It’ll come when Congress decides that delaying affordable medicine for profit is no longer acceptable.What This Means for Patients

If you’re waiting for a generic version of your prescription, you’re not just waiting for production to ramp up. You’re waiting for a legal system to catch up. That delay isn’t accidental. It’s designed. And it’s expensive. The next time you hear about a drug company “launching a new generic,” ask: Why did it take so long? And who benefited from the wait? The answer isn’t just legal. It’s personal.What is the Hatch-Waxman Act and how does it affect generic drugs?

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created a legal pathway for generic drug approval while protecting brand-name patents. It lets generic companies file ANDAs with Paragraph IV certifications to challenge existing patents. If the brand company sues within 45 days, the FDA must delay approval for up to 30 months. This system was meant to balance innovation and competition, but it’s now used to delay generic entry for years.

What is the Orange Book and why is it controversial?

The Orange Book is the FDA’s official list of patents linked to brand-name drugs. Only patents covering the active ingredient, formulation, use, or manufacturing should be included. But many companies list patents on delivery devices, packaging, or software-things unrelated to the drug itself. These improper listings trigger new lawsuits and 30-month delays. A 2025 court ruling clarified that such patents can be removed, but many remain on the list.

What are pay-for-delay settlements in generic drug litigation?

Pay-for-delay settlements occur when a brand-name company pays a generic manufacturer to delay launching its version of the drug. The FTC calls these anti-competitive, but studies show they often result in generics entering the market years earlier than they would if the generic company never filed a challenge. Without the settlement, many generic companies avoid filing ANDAs altogether due to legal risk.

Why is the Eastern District of Texas a hotspot for patent lawsuits?

The Eastern District of Texas has become the top venue for pharmaceutical patent litigation, handling 38% of all cases in 2024. Its judges are experienced in complex patent cases, procedures are predictable, and juries are seen as more sympathetic to patent holders. Many companies file there not because of where they’re based, but because it increases their chances of winning or securing favorable settlements.

How do patent thickets delay generic drugs?

Patent thickets are when a single drug is protected by dozens or even hundreds of overlapping patents. For example, semaglutide products have 152 patents. Even after the original patent expires, new ones can be filed or listed in the Orange Book, each triggering a new 30-month stay. This creates a chain of delays, making it nearly impossible for generics to enter until years after the drug should have become affordable.

What’s being done to fix this system?

The FTC has challenged over 500 improper Orange Book listings since 2024 and issued warning letters to major drug companies. The FDA is also set to implement new rules in 2026 requiring brand companies to certify under penalty of perjury that every listed patent meets legal standards. Generic manufacturers are increasingly using inter partes review (IPR) to challenge patents outside court. But without congressional reform, the 30-month stay and patent listing loopholes will continue to block affordable drugs.

Comments

Kane Ren

This system is insane. I’ve been waiting for a generic of my asthma inhaler for over two years. My copay is still $80. Meanwhile, the brand company just released a new version with a different color. Seriously? We’re paying for packaging now?

It’s not about innovation-it’s about greed dressed up as law.

November 23, 2025 at 08:46

Charmaine Barcelon

Wow. Just… wow. This is criminal. They’re literally holding people hostage for profit. And the courts? They’re in on it. The FDA? Sleeping. And you call this a free market? It’s a rigged game. And I’m done pretending it’s not.

November 25, 2025 at 02:25

Karla Morales

Per the FTC’s 2024 report: $13.9B annually lost to delayed generics. That’s 1.4% of total U.S. healthcare spending. The Eastern District of Texas accounted for 38% of pharma litigation - up from 12% in 2014. Orange Book abuse: 15–20% of listings likely invalid per Skadden’s 2025 analysis. And yet, no systemic reform. 🤷♀️

Meanwhile, Fish & Richardson’s revenue jumped 37%. Coincidence? I think not.

November 25, 2025 at 09:47

Javier Rain

Listen - I get that patents are important. But when a company files 150 patents on one drug just to keep generics out? That’s not protecting innovation. That’s engineering monopoly.

We need to break this cycle. Congress needs to cap the 30-month stay. The FDA needs to audit the Orange Book like it’s a bank ledger. And patients? We need to stop being quiet about this. Your life isn’t a legal loophole.

November 26, 2025 at 21:03

Laurie Sala

I just lost my dad to diabetes… and he couldn’t afford the insulin generic because the patent was ‘extended’ via a software update on the pen… I’m crying while typing this… how is this legal? How?!?!?!

November 28, 2025 at 05:43

Lisa Detanna

I grew up in India, where generics are available within months of patent expiry. We don’t have this mess. Why? Because their system doesn’t let companies game the law like this.

It’s not about being anti-American. It’s about being pro-human. If a drug’s patent expires, the medicine should be affordable. Period.

Let’s stop pretending this is about science. It’s about power.

November 29, 2025 at 23:50

Demi-Louise Brown

The Hatch-Waxman Act was a compromise. But compromise doesn’t mean surrender. The 30-month stay was meant to be a pause, not a prison. And the Orange Book was meant to be a map, not a maze.

Reform isn’t radical. It’s remedial. The FDA’s new perjury rule is a start. But real change requires Congress to stop taking money from the pharmaceutical lobby.

Patients aren’t the enemy. Profit is.

November 30, 2025 at 10:41

Matthew Mahar

so like… the patent thickets are basically legal spam? like you file 200 patents so the generics get stuck in a loop of lawsuits and just give up?? that’s not innovation that’s just being a jerk with a law degree 😭

also why is texas the patent playground?? like is there a sign there that says ‘come here if you wanna win’??

December 1, 2025 at 13:23

Bryson Carroll

Let’s be honest - this isn’t about patients. It’s about lawyers. The entire system is a revenue stream for law firms. You think Teva cares if you get your insulin cheaper? No. They care if their quarterly earnings hit the target. The FDA? They’re just bureaucrats with a stamp. Congress? They’re on the payroll.

Don’t waste your energy hoping for reform. The machine is designed to grind people down. Accept it.

December 3, 2025 at 06:48

Jennifer Shannon

You know what’s wild? When I was in med school, we were taught that patents were a trade-off - 20 years of exclusivity for the public getting the drug info. But now? The drug info is public, the patent’s expired, and they’re still blocking generics with patents on the *box* the drug comes in.

It’s like buying a car, then the company suing you because you tried to replace the radio. The radio wasn’t part of the engine. The patent shouldn’t cover the packaging.

And yet… here we are. We’ve turned healthcare into a legal horror movie. And the worst part? No one’s scared enough to change it.

December 3, 2025 at 14:12

Suzan Wanjiru

Inter partes review (IPR) was supposed to be the solution - cheaper, faster, PTAB over courts. But now the Supreme Court made it harder for generics to even file. So now the only people who can afford to fight are the ones who already have the money.

That’s not justice. That’s a tax on the desperate.

December 5, 2025 at 01:35

Kezia Katherine Lewis

It’s important to contextualize this within the broader framework of regulatory capture. The FDA’s Orange Book is not merely a registry - it is a legally enforceable instrument under 21 U.S.C. § 355(b)(1), and its misuse constitutes a violation of the Administrative Procedure Act’s requirement for reasoned decision-making.

Furthermore, the proliferation of patent thickets correlates with the increasing financialization of pharmaceutical R&D - where IP portfolios are treated as asset classes rather than public health tools.

Without structural intervention, market-based solutions will remain inequitable.

December 5, 2025 at 14:36

Henrik Stacke

Having lived in both the US and the UK, I can say this: the NHS doesn’t have this problem. Generics arrive within weeks. Why? Because the government negotiates prices and doesn’t let patent trolls dictate access.

Here, we’ve outsourced healthcare policy to lawyers and lobbyists. It’s not capitalism - it’s corporatism.

And frankly? I’m embarrassed for my country.

December 6, 2025 at 09:46

Manjistha Roy

As someone from India where generic drugs save millions, I see this as a moral failure. The same pills, same science, same efficacy - but in the US, people die waiting because of paperwork and lawsuits. This isn’t economics. This is ethics.

Every delay is a life postponed. Every patent on a dose counter is a betrayal of medicine’s promise.

December 7, 2025 at 07:10

Write a comment