When a generic drug hits the market, it’s not set in stone. Even small changes to how it’s made can trigger a full FDA re-evaluation. Many assume that once a generic drug is approved, it’s business as usual. But that’s not true. If you tweak the manufacturing process, switch suppliers, or upgrade equipment, the FDA may demand a new review - even if the pill looks and works the same. Understanding what triggers this re-evaluation isn’t just for regulators. It affects drug availability, pricing, and whether you can get your medication on time.

What Changes Actually Require FDA Approval?

Not every change to a generic drug’s production needs a full FDA review. The agency sorts changes into three buckets: Prior Approval Supplements (PAS), Changes Being Effected (CBE), and Annual Reports (AR). Only PAS changes need FDA green light before you make the switch. These are the big ones - the kind that could affect safety, strength, or how your body absorbs the drug.Here’s what counts as a PAS trigger:

- Switching from batch to continuous manufacturing

- Changing the drug’s active ingredient source (API) to a new facility or country

- Modifying the synthesis route for the active ingredient

- Increasing batch size by more than 25%

- Changing the formulation - like swapping one excipient for another

- Transferring production to a new factory

- Adding or removing a critical in-process control

These aren’t minor tweaks. They’re changes that could alter how the drug dissolves, breaks down, or interacts with your body. The FDA doesn’t assume safety. They want proof - analytical data, stability studies, and sometimes even new bioequivalence tests.

Why Does the FDA Care So Much?

Generic drugs aren’t copies. They’re exact replicas - chemically identical to the brand-name version, and proven to work the same way in your body. That’s why the FDA requires bioequivalence. But if you change how you make it, you might break that equivalence without realizing it.Take a 2022 case from a major generic maker. They increased batch size by 30% to cut costs. The pill looked fine. Lab tests showed the same active ingredient. But the dissolution profile changed slightly - meaning it released the drug slower in the body. The FDA flagged it. They required six months of new stability data and a full bioequivalence study. Approval took 14 months. The company lost millions in revenue during that time.

The FDA’s job isn’t to block innovation. It’s to make sure no change, no matter how small, compromises the drug’s performance. A 2023 FDA report showed that 68.4% of PAS submissions for manufacturing changes got a complete response letter - meaning the FDA asked for more data. The most common reasons? Analytical method changes, facility transfers, and formulation tweaks.

How Do Manufacturers Decide What Category Their Change Belongs To?

This is where things get messy. Companies often struggle to classify their own changes. A 2023 survey of 127 generic manufacturers found that 78.4% had trouble deciding whether their change needed a PAS, CBE, or AR. Small companies with fewer than five approved generics were 43% slower to get approval than big players with over 20.Why? Big companies have teams dedicated to regulatory strategy. They know the FDA’s gray areas. They schedule pre-submission meetings. They use Quality by Design (QbD) principles - building flexibility into the original ANDA so future changes are less risky.

For example, if you design your tablet compression process with a wide “design space” - meaning you know exactly which pressure, speed, and temperature ranges still produce a stable product - you can tweak those parameters later without triggering a PAS. That’s the goal of QbD. But most manufacturers don’t start there. They build the simplest version possible to get approval fast. Then, when they need to scale up or fix a supply issue, they hit a wall.

What’s the Real Cost of a Manufacturing Change?

It’s not just time. It’s money. The average cost of a PAS submission is $287,500, according to 2023 industry data. That’s not counting internal labor, validation studies, or lost sales during the delay. For a low-margin generic drug that sells for pennies per pill, that’s a hard pill to swallow.That’s why many companies avoid improvements - even ones that could make production safer or more reliable. One quality assurance professional on Reddit described a tablet press upgrade that took 18 months to approve. The new machine was faster, more precise, and reduced defects. But the FDA required a full PAS. The company decided to stick with the old press.

It’s a vicious cycle. Manufacturers don’t invest in better tech because the regulatory path is too slow and expensive. The FDA doesn’t see innovation because manufacturers aren’t submitting changes. Meanwhile, patients face shortages when one facility fails and no one can quickly switch production.

New FDA Programs Are Changing the Game

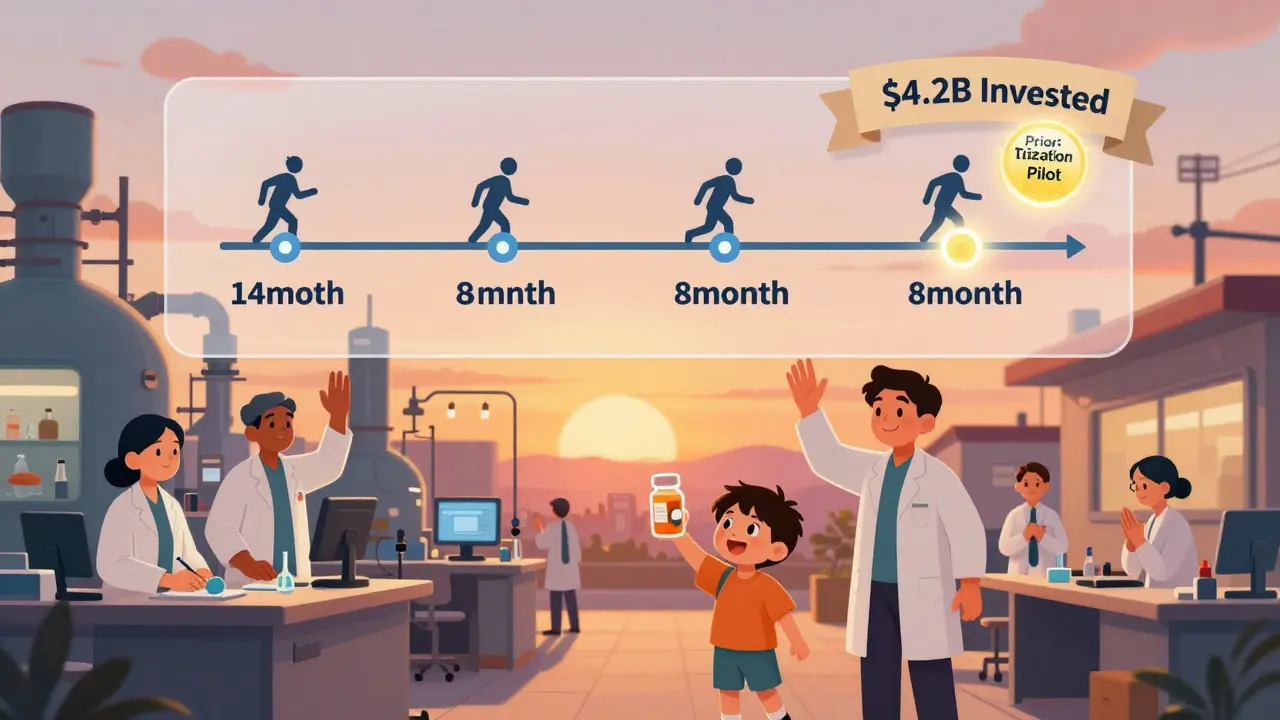

The FDA knows this problem exists. That’s why they launched the ANDA Prioritization Pilot Program in September 2023. If your generic drug is made in the U.S., uses U.S.-sourced active ingredients, and has U.S.-based bioequivalence data, you can get your PAS reviewed in 8 months instead of the usual 10-14.That’s a game-changer. The FDA’s goal? To bring $4.2 billion in new U.S. manufacturing investment by 2027. And it’s working. In 2024, Teva Pharmaceuticals got approval for its amlodipine continuous manufacturing line in just 8 months - thanks to pre-submission meetings and deep data packages.

Another new tool? The PreCheck program, announced in February 2024. It’s a two-phase review for high-priority facilities. Instead of waiting 18 months for a facility transfer inspection, you can now get it done in 9 months. That’s huge for companies trying to move production from overseas to the U.S.

And it’s not just about speed. The FDA’s draft guidance from January 2024 proposes a tiered risk system for complex generics - like injectables or peptide drugs. Minor changes might no longer need a PAS. That could cut PAS submissions by up to 35% for these high-complexity products.

What Should Generic Manufacturers Do Now?

If you’re making generic drugs, here’s what you need to do:- Map your current process. Know every step, every parameter, every control point. Document it like your life depends on it - because it does.

- Use QbD principles. Don’t just meet minimum specs. Build in flexibility. Define your design space early.

- Invest in PAT. Process Analytical Technology lets you monitor quality in real time. Companies using PAT saw 32.6% fewer PAS submissions over five years.

- Plan ahead for changes. Don’t wait for a failure to act. If you think you’ll need to scale up or switch suppliers in two years, start the regulatory prep now.

- Engage with the FDA. Schedule pre-submission meetings. Ask for feedback before you submit. Don’t guess what they want.

The goal isn’t to avoid change. It’s to make change predictable. The FDA isn’t your enemy. They just need proof that your change won’t hurt patients. If you give them that proof upfront, they’ll move faster.

What’s Next for Generic Drug Manufacturing?

GDUFA IV - the next round of user fee negotiations - starts in 2025. Industry groups are pushing for standardized change classification rules. Right now, one FDA division might call a change a PAS, while another says it’s a CBE. That inconsistency creates confusion and delays.McKinsey & Company estimates that by 2030, manufacturers who adopt advanced manufacturing tech and better regulatory strategies could save $8.7 billion annually in lost revenue from delays. That’s not theoretical. It’s happening now.

The future of generic drugs isn’t about cheaper pills. It’s about smarter manufacturing. The companies that invest in process understanding, data transparency, and FDA collaboration will win. The ones that treat the FDA as a hurdle will keep getting stuck.

For patients, this matters. When manufacturers can make changes quickly and safely, supply chains stay strong. When shortages happen, replacements arrive faster. And when drugs are made closer to home - in the U.S. - we’re less vulnerable to global disruptions.

Manufacturing changes aren’t a threat to generic approval. They’re part of its evolution. The question isn’t whether you should change - it’s how you change, and whether you’re ready for the review.

What happens if I make a manufacturing change without submitting a supplement?

Making a change without submitting the required supplement is a regulatory violation. The FDA can issue warning letters, halt shipments, or even withdraw your drug’s approval. Even if the product is identical, the law requires you to notify them. Ignoring this puts your entire business at risk.

Do all generic drugs need the same level of review for manufacturing changes?

No. Simple generics - like oral tablets with well-understood ingredients - often face fewer hurdles. Complex generics, such as inhalers, injectables, or peptide-based drugs, require stricter scrutiny. The FDA treats them like new drugs because their performance is harder to replicate. A change in a peptide drug’s impurity profile, for example, must stay under 0.5% and require full justification.

How long does a PAS review typically take?

Standard PAS reviews take about 10 months on average. But complex changes - like facility transfers or new synthetic routes - can take 14 months or longer. Under the new Prioritization Pilot Program, eligible U.S.-based manufacturers can get approval in as little as 8 months.

Can I use the same bioequivalence data for multiple manufacturing changes?

No. Each significant manufacturing change requires new bioequivalence data unless you can prove the change doesn’t affect drug release or absorption. The FDA requires direct comparison between the pre-change and post-change product. Even if your old data looks similar, they need fresh evidence.

Are there any shortcuts for small manufacturers?

There aren’t official shortcuts, but small manufacturers can reduce delays by using the FDA’s pre-submission meetings, joining industry coalitions for guidance, and focusing on QbD principles early. Some small companies partner with contract manufacturers who already have approved facilities to avoid facility transfer reviews altogether.

Comments

Shweta Deshpande

Wow, I never realized how fragile the generic drug supply chain is. One tiny tweak in the manufacturing process and suddenly you’re looking at a year-long delay? It’s wild how something so small can ripple into shortages that hit real people. I work in pharma logistics, and I’ve seen warehouses empty because one plant couldn’t get approval to switch to a new mixer. Patients don’t care about regulatory buckets-they just need their meds.

It’s not just about cost. It’s about trust. If we can’t trust that a pill made in Ohio works the same as one made in India, we’re all losing.

QbD isn’t just a buzzword-it’s the only way forward. Build flexibility in from day one, or pay the price later.

January 26, 2026 at 21:52

Jessica Knuteson

Regulation isn’t the problem. Complacency is.

January 27, 2026 at 07:49

Angie Thompson

Okay but can we talk about how insane it is that a company upgraded to a machine that reduces defects by 40%... and then chose to keep the old one because the FDA took 18 months to approve it? 😳

This isn’t innovation. This is punishment for trying to do better. We’re literally rewarding mediocrity because bureaucracy moves slower than molasses in January. And patients? They’re the ones holding the bag.

Also-PAT tech? YES. YES. YES. Why aren’t we funding this like it’s a moon landing?!

January 27, 2026 at 21:00

rasna saha

This is so true. I’ve seen small labs shut down because they couldn’t afford the PAS fees. No one talks about how this crushes the little guys. Big pharma has teams for this. Small ones? One overworked QA person trying to decipher FDA jargon while their coffee goes cold.

Pre-submission meetings should be mandatory. And free. For everyone.

January 28, 2026 at 10:48

Faisal Mohamed

The entire framework is archaic. You’re applying a Class I medical device paradigm to complex generics. The regulatory taxonomy hasn’t evolved with the science. QbD is a band-aid on a hemorrhage. What we need is risk-based adaptive pathways-leveraging real-time analytics and digital twins to enable continuous verification, not batch-based approval cycles. The FDA’s still operating in 2008 while the industry moved to 2024.

January 29, 2026 at 10:49

Josh josh

so like… if i change the color of the pill, does that count as a pas? 😅

January 31, 2026 at 00:54

Rakesh Kakkad

As someone from India where 80% of API comes from, I’ve seen the fallout. A facility in Telangana switched suppliers for citric acid-no change in purity, no change in dosage. FDA demanded a full bioequivalence study. Six months. Cost: $320k. The company folded.

We’re not just regulating drugs-we’re regulating geopolitics. And the patients? They’re collateral.

Why not allow equivalence by chemistry + process control data alone? Why force expensive clinical trials for every minor supplier change? It’s not science. It’s fear.

January 31, 2026 at 10:17

Simran Kaur

My cousin is on a generic blood pressure med. Last year, it disappeared for four months. No warning. No notice. Just… gone. We called the pharmacy. They said, ‘Oh, the manufacturer changed the tablet press. FDA put a hold.’

I cried. Not because I’m dramatic-but because I realized: our lives are held hostage by paperwork.

It’s not about profit. It’s about people. That pill isn’t just a chemical. It’s a morning ritual. A heartbeat. A mother’s peace of mind.

Can we please stop treating patients like an afterthought in a regulatory flowchart?

February 1, 2026 at 09:09

Neil Thorogood

Let me get this straight: You can’t upgrade a machine that reduces defects… unless you spend $300k and wait 14 months? And this is the land of the free?

Bro. We have drones that deliver pizza in 12 minutes. But a pill that dissolves 0.2 seconds slower? That’s a national emergency.

Someone get Elon on the phone. He’ll fix this with a SpaceX rocket and a blockchain ledger.

February 3, 2026 at 07:00

Aurelie L.

It’s all a scam. The FDA’s just protecting Big Pharma’s profits. If generics were easy to change, prices would drop even more. So they make it hard. Simple.

February 4, 2026 at 22:13

John Wippler

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: We treat drugs like they’re static objects. But biology isn’t static. Neither is manufacturing. The FDA’s system assumes that if two pills look the same, they’re the same. But absorption? Dissolution? Microstructure? Those aren’t visible. They’re emergent properties.

That’s why we need data-not just documents. We need real-time, continuous quality assurance. Not batch testing. Not post-hoc analysis. Live monitoring.

Until we stop thinking in boxes and start thinking in flows, we’ll keep having these disasters. The pill isn’t the product. The process is.

February 4, 2026 at 23:19

Skye Kooyman

So… if I make a change and don’t tell them… and nothing changes in my body… is it still illegal?

February 6, 2026 at 16:38

Robin Van Emous

It’s funny how we blame the FDA, but we don’t fund them. They’re understaffed, underpaid, and asked to be both scientist and cop. Meanwhile, companies submit half-baked dossiers and then act shocked when they get a complete response letter.

Maybe the problem isn’t the rules. It’s the lack of respect for the process.

Invest in quality. Talk to the FDA early. Don’t wait until your plant is on fire.

February 7, 2026 at 07:33

Joanna Domżalska

Everyone’s acting like the FDA is the villain. But what if they’re right? What if even ‘minor’ changes cause silent harm? We don’t have long-term data on 500+ modified generics. Maybe the system works because it’s paranoid. And maybe that’s okay.

February 7, 2026 at 22:19

Write a comment