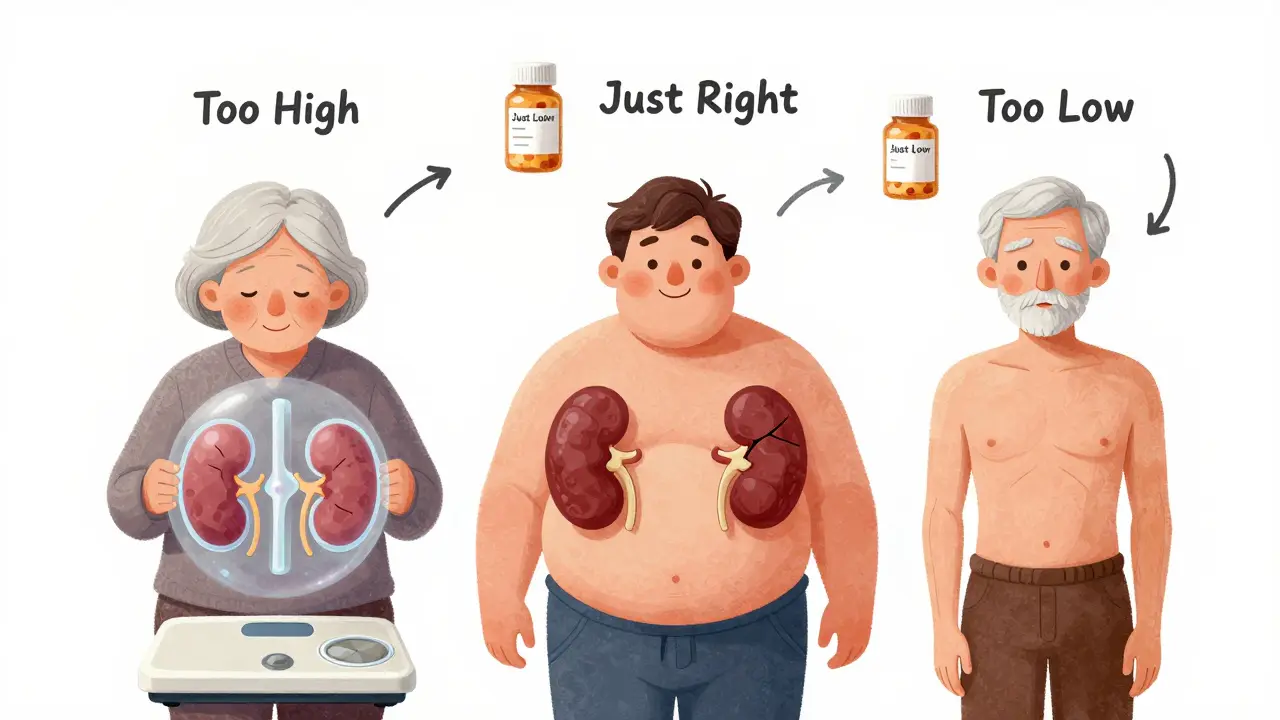

Getting the right dose of medicine isn’t just about following the label. For many people, the standard dose on the bottle can be too much-or too little-because of their age, weight, or how well their kidneys are working. This isn’t guesswork. It’s science. And getting it wrong can mean serious side effects, hospital visits, or even death.

Why One Size Doesn’t Fit All

Think of your body like a car. A 2000-pound sedan doesn’t need the same fuel mix as a 5000-pound truck. Your body works the same way with medicine. The amount of drug your body can handle depends on how much space it has to spread out (volume of distribution), how fast it can break it down (metabolism), and how quickly it can flush it out (clearance). That’s where age, weight, and kidney function come in.As we get older, our kidneys naturally slow down. By age 70, most people have lost about 30-40% of their kidney function-even if their blood tests still look "normal." That means drugs like antibiotics, painkillers, or heart medications stay in the body longer. Same with weight. Someone who weighs 120 pounds and someone who weighs 280 pounds don’t process the same amount of drug the same way. And if your kidneys aren’t filtering well, even a small dose can build up to toxic levels.

According to the National Kidney Foundation, 1 in 7 American adults has chronic kidney disease. That’s 37 million people. And for most of them, at least half the medications they take need a dose change. Yet, studies show that more than two-thirds of patients with kidney problems still get the wrong dose.

Kidney Function: The Most Critical Factor

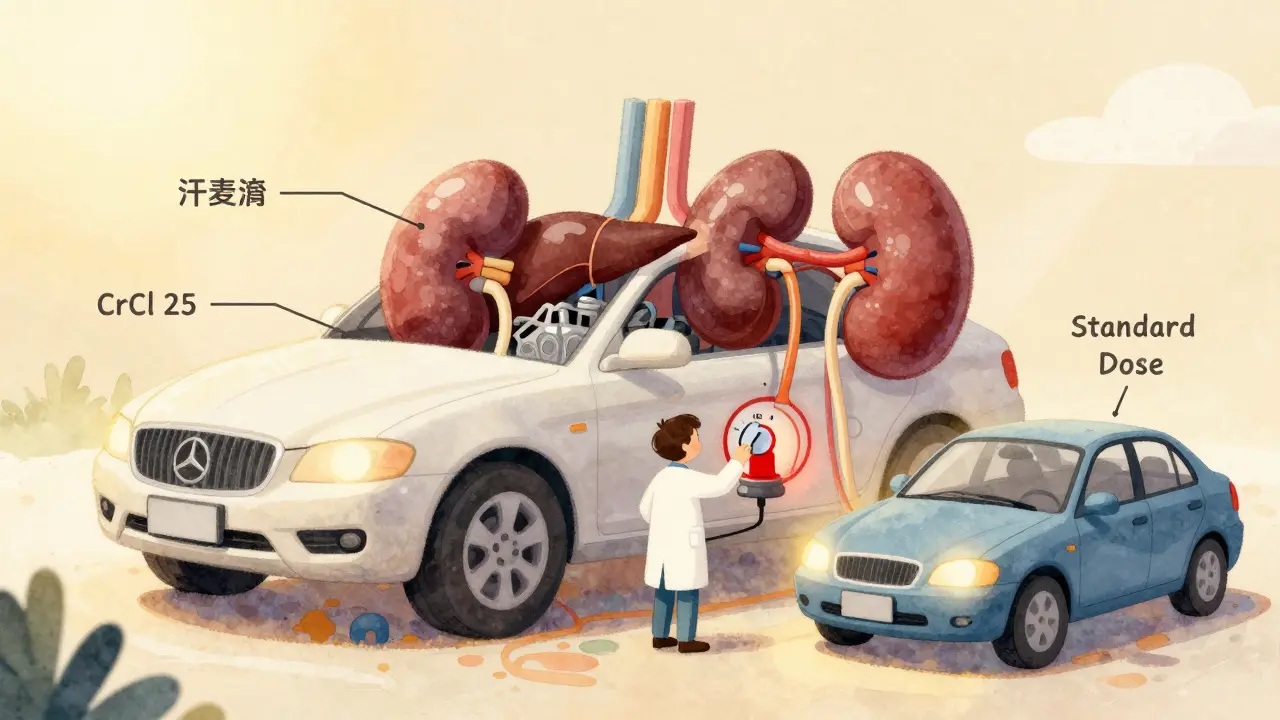

Your kidneys are the main cleanup crew for most drugs. If they’re not working right, the drug lingers. That’s why doctors don’t just look at your serum creatinine level-they calculate your creatinine clearance (CrCl) or estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).There are two main formulas used. The Cockcroft-Gault equation has been around since 1976. It uses your age, weight, sex, and serum creatinine to estimate how fast your kidneys are clearing creatinine from your blood. It’s still used in 85% of FDA drug labels because it’s been tested with real drug dosing data over decades.

The CKD-EPI equation, introduced in 2009, is more accurate for estimating kidney function overall, especially in people with normal or mildly reduced kidney function. But here’s the catch: most drug dosing guidelines were built using Cockcroft-Gault numbers, not CKD-EPI. So even if your doctor uses CKD-EPI to stage your kidney disease, they still need to convert it to CrCl to adjust your meds.

Here’s what the stages mean for dosing:

- eGFR ≥90 (Stage 1): Kidneys are damaged, but still working fine. Usually no dose changes needed.

- eGFR 60-89 (Stage 2): Mild reduction. Most drugs are fine at standard doses.

- eGFR 45-59 (Stage 3a): Moderate reduction. Some drugs need lower doses or longer gaps between doses.

- eGFR 30-44 (Stage 3b): Moderate to severe. Many drugs require significant adjustments.

- eGFR 15-29 (Stage 4): Severe. Only use drugs that are safe at low doses.

- eGFR <15 (Stage 5): Kidney failure. Most drugs need major changes or are avoided entirely.

For example, metformin-a common diabetes drug-is usually stopped if eGFR drops below 30. But some patients are kept on it at 500 mg once daily even with an eGFR of 28, which is dangerous. One pharmacist on Reddit reported catching a patient who’d been on 1000 mg twice daily for six months with an eGFR of 28. That’s a near-miss that could’ve led to lactic acidosis-a life-threatening condition.

Weight Matters-More Than You Think

If you’re overweight, your body doesn’t just hold more water-it holds more fat. And drugs behave differently in fat versus muscle. That’s why doctors don’t just use your actual weight. They use adjusted ideal body weight (AIBW).Here’s how it works:

- Calculate your ideal body weight (IBW):

- Men: 50 kg + 2.3 kg for every inch over 5 feet

- Women: 45.5 kg + 2.3 kg for every inch over 5 feet

- Then use this formula: AIBW = IBW + 0.4 × (actual weight − IBW)

For example, a 6-foot-tall man weighing 120 kg (265 lbs) has an IBW of 79 kg. His AIBW would be 79 + 0.4 × (120 − 79) = 95.4 kg. That’s the weight you plug into the Cockcroft-Gault equation-not his real weight, not his IBW.

Why? Because if you use actual weight in obese people, you’ll overestimate kidney function by 15-20%. That means you’ll give too high a dose. Studies show that using actual weight in obese patients leads to underdosing of antibiotics, which can cause treatment failure and drug resistance.

On the flip side, if you’re underweight (BMI <18.5), Cockcroft-Gault overestimates your kidney function by up to 25%. That means you might get a dose that’s too high. CKD-EPI handles low body weight better, but again-most drug guidelines are based on CrCl.

Age Isn’t Just a Number

People over 65 are the most likely to get dosing errors. Why? Because their kidneys aren’t just slower-they’re also less able to handle sudden changes. A 70-year-old with an eGFR of 50 might have had an eGFR of 90 at 40. That’s a big drop. But if their doctor only looks at the number without considering the trend, they might not adjust the dose.Also, older adults often take 5-10 medications. Each one competes for the same cleanup pathways. A simple painkiller like ibuprofen can reduce kidney blood flow, making things worse. And many drugs for dementia, anxiety, or sleep-like benzodiazepines or anticholinergics-are cleared by the kidneys. Even small doses can cause confusion, falls, or delirium.

One study found that 30% of adverse drug events in older adults happen because of improper dosing in kidney disease. That’s not rare. That’s common. And it’s preventable.

What Happens When Dosing Goes Wrong

The consequences aren’t theoretical. They’re real, and they’re costly.- Vancomycin, a powerful antibiotic, is dosed by CrCl. If you give a standard dose to someone with Stage 3B CKD, you might not reach the level needed to kill the infection. That’s what happened in a Chicago hospitalist’s case-three patients got subtherapeutic doses because their eGFR was used instead of CrCl.

- Insulin and sulfonylureas for diabetes can cause dangerous low blood sugar in kidney patients because they’re cleared slower. A 2023 survey found 22% of dosing errors involved diabetes meds.

- Anticoagulants like warfarin and direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) need careful adjustment. Too much? Risk of bleeding. Too little? Risk of stroke.

And here’s the kicker: even hospitals with computerized systems make mistakes. A 2022 survey found that 68% of pharmacists see wrong renal doses at least once a week. Why? Because different references-Lexicomp, Micromedex, hospital formularies-give different recommendations. One pharmacist reported seeing five different doses for the same antibiotic at the same eGFR level.

How to Get It Right

There’s no magic bullet, but here’s what works:- Use Cockcroft-Gault for dosing-even if your lab reports eGFR. Convert it to CrCl using the formula: (140 − age) × weight × 0.85 (if female) / (serum creatinine × 72)

- Use adjusted body weight for anyone with BMI over 30. Don’t use actual weight.

- Check the drug’s label for renal dosing. Look for CrCl thresholds, not eGFR.

- Use clinical decision support. Hospitals with EHR alerts that flag renal dosing errors cut mistakes by 47%.

- When in doubt, lower the dose. It’s safer to underdose than overdose. You can always increase it later.

For example, if you’re prescribed cefazolin (an antibiotic) and your CrCl is 25 mL/min, the right dose might be 500 mg every 12 hours instead of 1 gram every 8 hours. But if your formulary says 750 mg every 8 hours, check another source. Don’t trust one reference.

The Future: Smarter, Personalized Dosing

The system isn’t perfect. But it’s getting better. The FDA is pushing for more precise dosing guidelines. In 2023, they released draft guidance recommending therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM)-measuring actual drug levels in blood-for 17 high-risk medications like vancomycin, aminoglycosides, and certain antivirals.Researchers are also testing AI tools that combine kidney function, genetics, age, weight, and even diet to predict the perfect dose. A $50 million NIH project is launching pilot programs in 2024 to test these systems.

Down the road, wearable sensors might measure kidney filtration in real time. Imagine a patch that tells your phone: "Your kidneys are filtering at 38 mL/min today. Adjust your metformin to 400 mg." That’s not sci-fi-it’s coming.

What You Can Do Today

If you’re on any regular medication and you’re over 60, overweight, or have been told you have kidney issues:- Ask your doctor: "What’s my creatinine clearance?" Not just eGFR.

- Ask: "Is my dose adjusted for my kidneys?"

- Ask your pharmacist: "Does this drug need a kidney adjustment?"

- Keep a list of all your meds and share it at every visit.

Don’t assume your dose is right just because you’ve been taking it for years. Kidney function changes. Weight changes. Age changes. Your dose should change too.

Medication safety isn’t about following instructions. It’s about understanding your body-and making sure your pills match it.

Comments

Jerry Rodrigues

Been on metformin for 12 years. My doc never checked my CrCl until I brought it up. Turned out my eGFR was 29 and I was on 1000mg twice daily. Scary stuff. They dropped me to 500mg once a day and I didn’t even notice a difference in blood sugar. Just goes to show you never assume.

Thanks for laying this out so clearly.

January 21, 2026 at 09:55

Uju Megafu

Of course the system is broken. Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know your kidneys matter. They profit off people getting sick from wrong doses. Why do you think they push eGFR over CrCl? Because it’s easier to ignore the math. Wake up.

Also, why do doctors still use weight-based dosing for obese people? Because they’re lazy. And you’re paying for it.

January 21, 2026 at 13:52

Jarrod Flesch

As a pharmacist in Sydney, I see this daily. One guy came in with a prescription for vancomycin - same dose as someone with normal kidneys. His CrCl was 22. I called the prescriber, they were shocked. Changed it to 750mg every 24h. He’s doing great now.

Pro tip: Always double-check the drug label. Lexicomp and Micromedex often disagree. I keep both open and pick the most conservative one. Safety first 😊

January 23, 2026 at 13:30

Amber Lane

My grandma’s on 5 meds. Two of them needed dose changes after her kidney test. She didn’t know. Neither did her doctor. This needs to be standard.

January 24, 2026 at 21:59

Gerard Jordan

Just shared this with my entire family. My uncle’s 74, diabetic, and on metformin. I sent him the eGFR vs CrCl chart. He called his doctor today and asked for a CrCl calculation. Got his dose lowered. He’s so relieved.

Also, if you’re over 60, ask your pharmacist to review ALL your meds. They’re the unsung heroes of safe dosing. 🙌

January 25, 2026 at 09:46

Roisin Kelly

So what? Doctors are idiots. I’ve been on the same dose for 8 years. My kidneys are fine. Why should I care about some formula? They’re just trying to control us with numbers. Next they’ll tell me how to breathe.

January 26, 2026 at 10:18

lokesh prasanth

CrCl is outdated. We need AI. Why use 1976 math when we have neural nets? Also, creatinine is not reliable. Muscle mass matters. But no one talks about that. #MedEdFail

January 26, 2026 at 12:30

Malvina Tomja

This post is dangerously oversimplified. The Cockcroft-Gault equation is racially biased, gender-biased, and ignores lean body mass. Using it in 2024 is medical malpractice. The CKD-EPI is the only scientifically valid tool. Anyone who recommends CrCl is perpetuating systemic inequity.

January 26, 2026 at 21:52

MAHENDRA MEGHWAL

As a clinical pharmacist in Mumbai, I can confirm that over 60% of elderly patients in our outpatient clinics receive inappropriate renal dosing. The root cause is not ignorance - it is time constraints and fragmented electronic records.

One solution: Integrate CrCl calculators directly into the e-prescribing system. Mandatory. No exceptions.

Thank you for highlighting this critical gap.

January 28, 2026 at 01:41

Ben McKibbin

Love how this breaks it down without jargon. But here’s the real kicker - most EHRs auto-populate eGFR and ignore CrCl. So even if your doctor knows better, the system pushes the wrong number. That’s not human error. That’s bad design.

And yes, using actual weight in obese patients? That’s like using the weight of a loaded cargo plane to calculate fuel for a bicycle. You’re gonna crash.

Also - if you’re on warfarin AND have CKD? Get your INR checked weekly. Don’t wait for the script to renew.

January 28, 2026 at 12:12

Jerry Rodrigues

^ This. I had a pharmacist flag my dose because the EHR auto-filled eGFR. My CrCl was 31. The system said "no adjustment needed." I had to manually override it. That’s not a feature. That’s a bug.

January 29, 2026 at 00:02

Write a comment