After an organ transplant, survival isn’t just about the surgery. It’s about the daily reality of taking pills that keep your body from attacking its new organ - but also weaken your defenses against everything else. For most transplant recipients, this means lifelong use of immunosuppressant drugs. These aren’t optional. Without them, rejection is almost certain. But the trade-off is a long list of side effects and dangerous drug interactions that can reshape your health in ways no one warns you about until it’s too late.

Why Immunosuppressants Are Non-Negotiable

Your immune system is built to fight foreign invaders. A transplanted kidney, liver, or heart? To your body, it’s an invader. Left unchecked, your immune system will destroy it. That’s why immunosuppressants are the backbone of transplant care. The first real breakthrough came in 1960 with azathioprine, which pushed one-year kidney graft survival from near zero to 50%. Then, in 1983, cyclosporine changed everything - jumping survival rates to 80-90%. Today, nearly all transplant recipients in the U.S. take a triple therapy: a calcineurin inhibitor (usually tacrolimus), an antimetabolite (like mycophenolate), and a steroid (like prednisone).Tacrolimus is the go-to drug. It’s used in 92.4% of kidney transplant cases in the U.S. Why? Because it works better than cyclosporine. The 2005 ELITE-Symphony trial showed 83.1% graft survival with tacrolimus versus 76.6% with cyclosporine. But better efficacy doesn’t mean fewer problems. Tacrolimus has a narrow window - too little and you reject the organ; too much and you damage your kidneys, nerves, or pancreas. Trough levels must be kept between 5-8 ng/mL in the first year, according to KDIGO guidelines. That’s a razor’s edge.

How These Drugs Work - and Where They Go Wrong

Each class of immunosuppressant hits a different target. Calcineurin inhibitors like tacrolimus and cyclosporine block T-cells from activating. Antimetabolites like mycophenolate and azathioprine starve immune cells of the building blocks they need to multiply. Steroids like prednisone shut down inflammation across the board. mTOR inhibitors like sirolimus slow cell growth.The problem? These drugs don’t know the difference between a rogue immune cell and a healthy one. They don’t target just the transplant. They suppress your entire defense system. That’s why infections become a constant threat. A simple cold can turn into pneumonia. A cut that heals in days for most people might turn into a serious infection for a transplant patient. The National Kidney Foundation found 85% of recipients report increased infection risk - and that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

The Hidden Danger: Drug Interactions

Most transplant patients take more than 10 medications a day. Blood pressure pills. Cholesterol drugs. Antibiotics. Pain relievers. Even over-the-counter supplements like St. John’s Wort or garlic pills. And nearly every one of them can mess with your immunosuppressants.Tacrolimus and cyclosporine are metabolized by the liver enzyme CYP3A4. Anything that blocks this enzyme - like antifungals (fluconazole), some antibiotics (clarithromycin), or even grapefruit juice - can cause tacrolimus levels to spike by 50% to 200%. That’s not a small bump. It’s a trip to the ER. On the flip side, drugs like rifampin (used for TB) or seizure meds like phenytoin can push levels down by 60-90%. That’s a fast track to rejection.

Even common painkillers like ibuprofen can be dangerous. They’re nephrotoxic. Combine that with tacrolimus - also nephrotoxic - and you’re stacking two kidney killers. Acetaminophen is safer, but still needs monitoring. And don’t forget herbal supplements. A 2020 review in Transplantation Direct found that 30-40% of commonly used medications interact with calcineurin inhibitors. That’s nearly half of everything your doctor might prescribe.

Side Effects That Change Your Life

The side effects aren’t just annoying - they’re life-altering.Nephrotoxicity is the most common. Up to 40% of kidney transplant recipients develop chronic kidney damage from calcineurin inhibitors. Protocol biopsies show 65% have scarring in the kidney tissue by year five. That’s not rejection - it’s the drug itself eating away at the organ you were trying to save.

New-onset diabetes after transplant (NODAT) hits 20-30% of tacrolimus users. That’s double the rate seen with cyclosporine. Suddenly, you’re not just managing one chronic condition - you’re managing two. Insulin shots. Carb counting. Blood sugar checks. It’s a second full-time job.

Gastrointestinal issues are rampant. Mycophenolate causes diarrhea in 32% of patients, nausea in 28%, and abdominal pain in 25%. That’s nearly half the people on this drug. Azathioprine is gentler on the gut but hits the bone marrow harder - 18% get low white blood cell counts, leaving them vulnerable to infections.

Steroids are the worst offenders for cosmetic and metabolic damage. 40-60% of long-term users develop osteoporosis. One in three will break a bone by age 60. Moon face. Buffalo hump. Weight gain of 15-20 pounds in six months. A Cleveland Clinic survey found 45% of patients struggled with how they looked in the mirror. One Reddit user wrote: “I didn’t recognize myself. I felt like a stranger in my own skin.”

Neurological side effects are underreported. Tremors from tacrolimus are common. Some patients say it’s like having a constant caffeine buzz. Others get headaches, insomnia, or even seizures. One user on r/transplant described “steroid rage” - sudden, uncontrollable anger that scared their family.

Trade-Offs Between Drugs

There’s no perfect drug. Each has its own set of trade-offs.Sirolimus (an mTOR inhibitor) is often used as a replacement for tacrolimus when kidney damage becomes a problem. In the CONVERT trial, patients switched to sirolimus saw their GFR improve by 2.1 mL/min/year versus a decline of 4.3 mL/min/year on tacrolimus. That’s real kidney protection. But sirolimus brings its own problems: 25% get protein in their urine, and 12% have delayed wound healing. Mouth ulcers are so common, patients call them “sirolimus sores.”

Belatacept, a newer drug approved for kidney transplants, cuts cardiovascular deaths by 30% and reduces cancer risk by 25% compared to tacrolimus. Sounds great? But it causes more acute rejection - 19% versus 7%. That means more hospital visits, more biopsies, more stress. It’s not for everyone.

And then there’s voclosporin, approved by the FDA in 2023. It’s a new calcineurin inhibitor with more predictable absorption. In trials, it caused 24% less kidney damage than tacrolimus - without sacrificing rejection control. But it’s expensive. And not yet widely available.

Managing the Daily Grind

Taking these drugs isn’t a one-time prescription. It’s a 24/7 routine.Most patients take 8-12 pills a day, at specific times. Miss a dose? Risk rejection. Take two by accident? Risk toxicity. Electronic pill dispensers have improved adherence from 72% to 89% in some programs. But they’re not magic. The real key is communication. The CareDx 2022 patient guide says it plainly: “It’s important to keep an open line of communication with your transplant team.”

Monitoring is relentless. Blood tests every week at first. Then monthly. Lipid panels every three months. Oral glucose tolerance tests every six months to catch diabetes early. Blood counts to watch for anemia or low white cells. You learn to recognize the signs: a fever above 100.4°F? Call your team immediately. Diarrhea that won’t quit? Don’t wait. Even a new rash could mean a drug reaction.

And lifestyle changes? They’re non-negotiable. No raw sushi. No undercooked eggs. No garden soil without gloves. Wear a mask in crowded places. Avoid people with colds. Live within two hours of your transplant center - 92% of U.S. programs require this for the first year. Why? Because rejection or infection can hit fast. You need to be able to walk into the hospital at 2 a.m.

The Bigger Picture: Survival and Quality of Life

Yes, transplants extend life. But they don’t restore it. Ten-year survival for kidney transplant recipients is 65%. For someone the same age who never needed a transplant? 85%. That gap hasn’t closed in decades.Why? Because the drugs that save the organ also shorten life. Cancer risk is 2-4 times higher. Skin cancers are the most common - 23% of liver transplant recipients get them. GI cancers and HPV-related cancers are 100 times more frequent than in the general population. The FDA recorded over 12,000 immunosuppressant-related adverse events in 2023. Two-thirds were infections. One in seven were cancers.

And yet, non-adherence is the second leading cause of late graft loss - responsible for 22% of failures. Why? Because the side effects are brutal. Fatigue. Weight gain. Mood swings. The constant fear of rejection. The weight of being a “medical case” forever.

Some experts argue we focus too much on side effects. That patients stop taking meds because they’re scared, not because they’re sick. Others say: “If the price of survival is losing your health, your dignity, your sleep - is it worth it?”

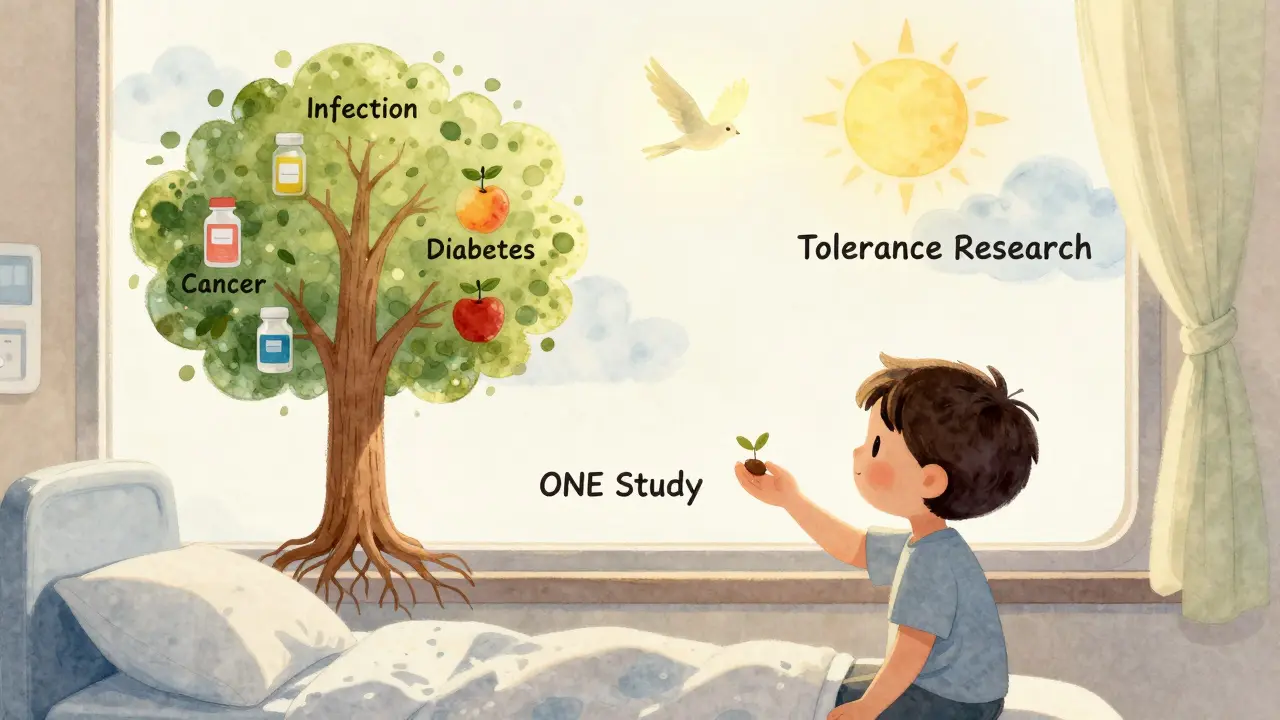

There’s no easy answer. But one thing is clear: we need better drugs. Research is moving toward tolerance induction - teaching the immune system to accept the transplant without drugs. Early trials show promise. In the ONE Study, 15% of kidney recipients achieved operational tolerance - meaning they stopped all immunosuppressants and kept their organ. That’s not a cure. But it’s a start.

What You Can Do Today

If you’re on immunosuppressants:- Keep a medication log. Write down every pill, supplement, and OTC drug you take. Show it to your team every visit.

- Never start a new drug without asking. Even something as simple as a cold remedy can be dangerous.

- Report changes fast. A new rash, unexplained fever, sudden weight gain, or mood shift - don’t wait.

- Ask about steroid minimization. If you’re low-risk, ask if you can stop prednisone early. Many centers now do this safely.

- Get vaccinated. Flu, pneumonia, COVID-19, shingles - all critical. Avoid live vaccines.

- Find your support group. Whether it’s Reddit, a local chapter, or a transplant buddy - you’re not alone.

Transplant recipients are survivors. But survival isn’t just about living longer. It’s about living well. And that means understanding the drugs that keep you alive - and knowing how to fight back against their cost.

Can I stop taking immunosuppressants if I feel fine?

No. Feeling fine doesn’t mean your immune system has stopped attacking the transplant. Most rejection episodes happen without symptoms until it’s too late. Stopping immunosuppressants - even for a day - can trigger rapid, irreversible rejection. This is not something to experiment with. Over 22% of late graft losses are due to non-adherence. If you’re struggling with side effects, talk to your transplant team. They can adjust your regimen, but never stop on your own.

Are generic immunosuppressants as effective as brand names?

For some drugs, yes. Generic cyclosporine (Gengraf) and mycophenolate (Myfortic) are FDA-approved and widely used. But for tacrolimus, brand-name Prograf is still preferred in most centers. Why? Because generic versions can have slight differences in absorption that affect blood levels. Even a 10% variation can be dangerous. If you’re switched to a generic, your drug levels must be monitored more closely for the first few weeks. Always confirm with your pharmacist and transplant team before switching.

Why do I need so many blood tests?

Because immunosuppressants have a narrow therapeutic window - the difference between too little and too much is small. Tacrolimus levels must be kept between 5-8 ng/mL in the first year. Too low? Rejection risk. Too high? Kidney damage, tremors, diabetes. Blood tests tell your team if your dose needs adjusting. Monthly CBCs catch low blood counts. Lipid panels monitor cholesterol spikes. Glucose tests catch diabetes early. These aren’t routine checks - they’re life-saving surveillance.

Can immunosuppressants cause cancer?

Yes. Long-term immunosuppression suppresses your body’s ability to detect and destroy abnormal cells. This increases the risk of skin cancers (especially squamous cell carcinoma), lymphoma, and HPV-related cancers like cervical and anal cancer. Liver transplant recipients have a 23% lifetime risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer. That’s why annual full-body skin checks are mandatory. Early detection saves lives. If you notice a new mole, sore that won’t heal, or unusual patch on your skin - get it checked immediately.

Is there hope for a future without lifelong drugs?

Yes - but it’s still experimental. Researchers are testing ways to train the immune system to accept the transplant without drugs. One promising approach uses regulatory T cells to teach the body tolerance. In the ONE Study, 15% of kidney recipients stopped all immunosuppressants and kept their organ for over two years. That’s not a cure for everyone - yet. But it’s proof that tolerance is possible. Clinical trials are expanding. For now, lifelong drugs are still the standard. But the goal is clear: transplant without drugs.

What’s Next?

The future of transplant medicine isn’t just about better drugs - it’s about smarter ones. Drugs that target only the immune response to the graft. Drugs that don’t wreck your kidneys, trigger diabetes, or raise your cancer risk. The 2024 American Transplant Congress highlighted new molecules in early trials that block rejection pathways without broad immune suppression. And with the patent for tacrolimus expiring in 2025, cheaper alternatives may become more accessible.But until then, the reality remains: you’re balancing two threats - rejection and side effects. And the only way to win is with knowledge, vigilance, and a team you trust. Don’t suffer in silence. Ask questions. Push for better options. Your life after transplant isn’t just about survival. It’s about reclaiming your life - one pill, one test, one conversation at a time.

Comments

Charles Barry

This is all just a government cover-up. The pharmaceutical companies own the FDA, the transplant centers, and your doctor. They want you addicted to these drugs because they make billions. That 'narrow therapeutic window'? Bullshit. They could make safer drugs but they won't. You think they care about your kidneys? Nah. They care about your monthly co-pay. Wake up. The real cure is already out there - it's just being suppressed. I've seen the documents. The data's buried. They're killing you slowly so you keep buying pills. #PharmaLies

December 23, 2025 at 05:41

Rosemary O'Shea

Oh please. This is such a pedestrian take on a profoundly complex medical reality. The entire discourse around immunosuppressants is reduced to a series of bullet points like some kind of patient pamphlet. Where’s the philosophical weight? The existential dread? The quiet horror of being a walking contradiction - your body saved by the very thing that erodes your essence? You don’t just take pills. You become a pharmacological monument to modern medicine’s grotesque elegance. And yet, no one dares speak of the loneliness of being both alive and alienated from your own skin.

December 24, 2025 at 04:21

Art Van Gelder

Man, I’ve been following transplant research since the early 2000s, and this is one of the most accurate summaries I’ve seen in a long time. The tacrolimus vs. cyclosporine data? Spot on. The drug interaction charts? Dead right. But what nobody talks about is how the system fails patients emotionally. You get this life-saving surgery, then you’re handed a 12-pill daily routine, a list of 47 foods you can’t eat, and told to ‘stay positive.’ Meanwhile, your insurance drops you after 18 months because you’re ‘high risk.’ I’ve seen friends lose their jobs because they needed a 3 p.m. blood draw. This isn’t medicine. It’s a full-time job with no PTO and no hazard pay. And the worst part? You’re grateful you’re alive - so you shut up and take the pills.

December 25, 2025 at 11:59

Kathryn Weymouth

There are several grammatical inconsistencies in the original post that undermine its credibility. For instance, the inconsistent use of serial commas, the improper placement of em dashes, and the overuse of passive voice in clinical descriptions. Additionally, the phrase 'a trip to the ER' is colloquial and inappropriate for a medical context. Proper terminology would be 'acute toxicity requiring emergency intervention.' While the content is factually accurate, the presentation lacks the precision required for a topic of this gravity. Transplant medicine deserves rigor - not Reddit-style sensationalism.

December 27, 2025 at 00:45

Nader Bsyouni

So we’re just supposed to accept that this is the price of life? That we trade our health for a few more years? What a joke. The whole system is rigged. You’re told to take these drugs forever but no one ever asks why your immune system hates your new organ in the first place. Maybe it’s not the organ. Maybe it’s the environment. Maybe it’s the toxins. Maybe it’s the stress. Maybe we’re all just broken. And the drugs? They’re just a bandage on a bullet wound. And they charge you $1,200 a month for it. The real transplant is the one that needs to happen - to the system. Not the kidney. Not the liver. The system.

December 27, 2025 at 16:32

Julie Chavassieux

My sister got a liver transplant in 2019. She’s been on tacrolimus since. She lost 30 pounds. Then gained 50. She got diabetes. Then neuropathy. Then depression. She cries every night. She doesn’t recognize herself. She doesn’t recognize me. And they tell her to ‘stay positive.’ Like that fixes it. Like that’s enough. I hate this. I hate that we’re told to be grateful. I hate that we’re told it’s a miracle. It’s not a miracle. It’s a fucking prison. And the key? It’s in the pill bottle. And the lock? It’s in your soul.

December 29, 2025 at 12:12

Vikrant Sura

Too long. Didn't read. But I saw the word 'tacrolimus' and I'm out. I don't trust anything that needs a blood test every week. Life's too short.

December 29, 2025 at 19:32

Candy Cotton

As an American citizen who has paid into this system for decades, I find it unacceptable that our nation's medical infrastructure is so dependent on foreign drug manufacturing. Tacrolimus is produced in India. Mycophenolate? China. And we wonder why our transplant patients face shortages? This is national security. We must bring pharmaceutical production back to the United States. We cannot rely on adversarial nations to keep our citizens alive. The FDA must mandate domestic sourcing. Period.

December 30, 2025 at 15:06

Jeremy Hendriks

Here’s the thing no one says out loud - we’re all just temporary vessels. The organ isn’t yours. The drugs aren’t yours. Even your thoughts aren’t entirely yours. You’re a host. A biological compromise. The transplant doesn’t save you - it redefines you. You become a walking archive of chemical adjustments, bloodwork, and fear. And the worst part? You’re proud of it. You wear your pill organizer like a medal. But it’s not a medal. It’s a cage. And you’re the jailer. And the prisoner. And the guard. All at once. That’s the real cost. Not the side effects. The identity erosion.

December 31, 2025 at 23:19

Ajay Brahmandam

Just wanted to say this is one of the clearest breakdowns I've seen on this topic. I'm a kidney transplant recipient from India and I've been on tacrolimus for 8 years. The drug interactions are real - I once took a turmeric supplement and my levels spiked. Had to go to the ER. The key is to keep a log and talk to your pharmacist. Also, avoid grapefruit like the plague. Seriously. And yes, the steroid face is real. I had to get a new wardrobe. But I'm alive. And I'm grateful. Don't give up. Your team is your lifeline.

January 1, 2026 at 16:00

Tarun Sharma

Thank you for the comprehensive overview. The data presented is consistent with clinical guidelines from the Asian Society of Transplantation. I would recommend supplementing this information with the 2023 KDIGO update on calcineurin inhibitor minimization protocols, particularly in Asian populations where metabolic complications are more prevalent. Adherence remains the most critical factor in long-term graft survival.

January 2, 2026 at 21:30

Aliyu Sani

yo this hit different. i got a liver in 2021 and i swear i feel like a cyborg now. my body is a server running on corrupted firmware and the meds are the patches. some days i feel fine, other days i just wanna scream into the void. the paranoia? real. the weight gain? real. the fact that i can’t eat a damn avocado without checking my levels? yeah. but i’m here. and i’m still typing. so i guess that counts. also… why does grapefruit juice feel like a betrayal?

January 4, 2026 at 00:35

Gabriella da Silva Mendes

OMG I CRIED reading this. 😭 This is literally my life. I take 14 pills a day. I have moon face. I broke my hip last year. I can’t even hug my grandkids without worrying I’ll get sick. And now I have to get a skin cancer screening EVERY SINGLE MONTH. I’m 42. I look 60. I’m not living. I’m surviving. And the worst part? Everyone says ‘You’re so strong!’ Like that’s supposed to make it better. No. I’m just tired. And I hate that I have to be grateful for this. 💔 #TransplantLife #ImmunosuppressantStruggles

January 4, 2026 at 02:12

Jim Brown

There is a metaphysical dimension to transplantation that transcends pharmacology. We speak of organs as if they are mere biological components, yet they carry the essence of another’s life - their breath, their hunger, their silence. To take a heart, a liver, a kidney - is to accept a fragment of another’s soul into the architecture of your own. The drugs do not merely suppress immunity; they enforce a covenant of silence between donor and recipient. We are not just surviving - we are becoming hybrid beings. And perhaps, in this quiet fusion, lies the most profound mystery of modern medicine: not how we keep the organ alive, but how we learn to live with the ghost inside us.

January 5, 2026 at 23:26

Write a comment