Amantadine isn’t a drug you hear about every day, but for decades it played a quiet but important role in fighting flu and even helping with Parkinson’s symptoms. Back in the 1960s, it was one of the first antiviral drugs approved for use in humans. Today, it’s rarely used for flu anymore-but understanding how it works still matters, especially as new viruses emerge and old ones come back in unexpected ways.

How Amantadine Stops Influenza A

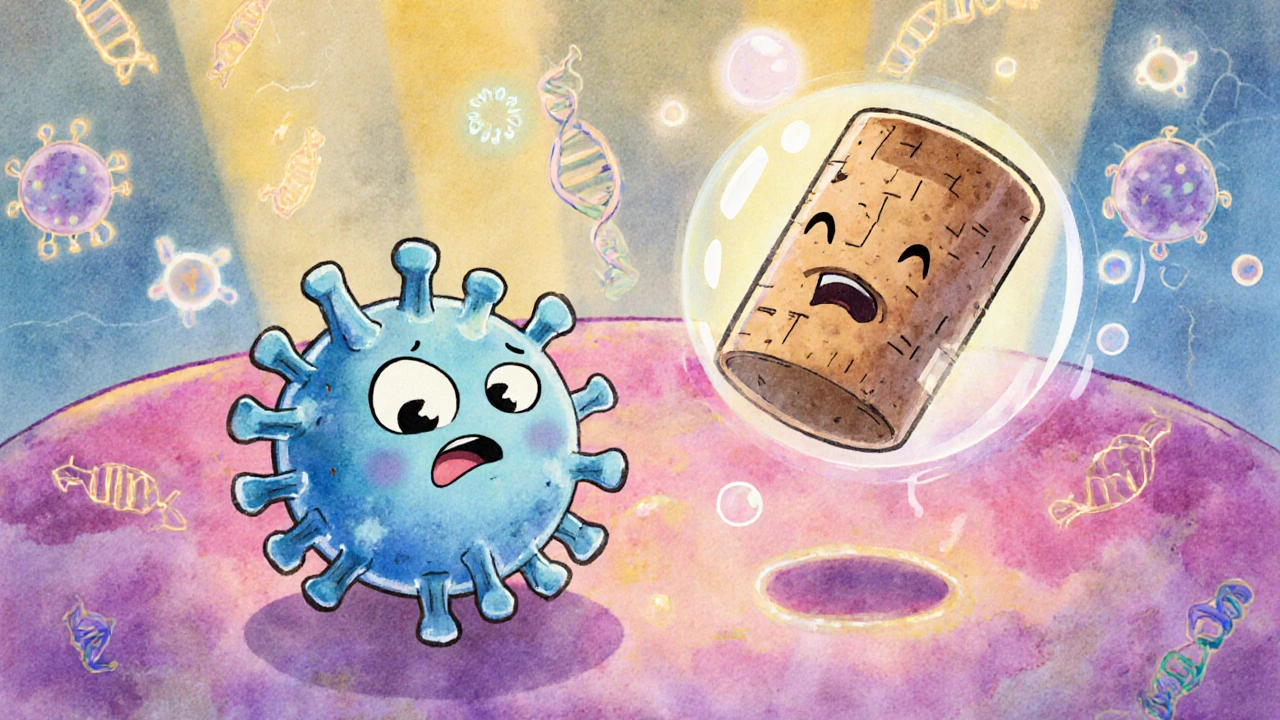

Amantadine works by targeting a very specific part of the influenza A virus: the M2 ion channel. This tiny protein hole sits in the virus’s outer shell. When the virus enters a human cell, it needs to drop its genetic material inside. To do that, it uses the M2 channel to let protons (hydrogen ions) flow into its core. That acidification triggers the virus to unzip its genetic code and start copying itself.

Amantadine slips into that M2 channel like a cork in a bottle. It blocks the protons from getting in. Without that acid boost, the virus can’t release its RNA. It’s stuck. The virus can’t replicate. The infection doesn’t spread.

This mechanism was groundbreaking when it was discovered. Before amantadine, doctors had no real way to stop the flu after someone got sick. Vaccines helped prevent it, but once you were infected, it was mostly rest and fluids. Amantadine changed that. It could shorten flu symptoms by about a day if taken within 48 hours of the first signs-fever, chills, muscle aches.

Why It’s Not Used for Flu Anymore

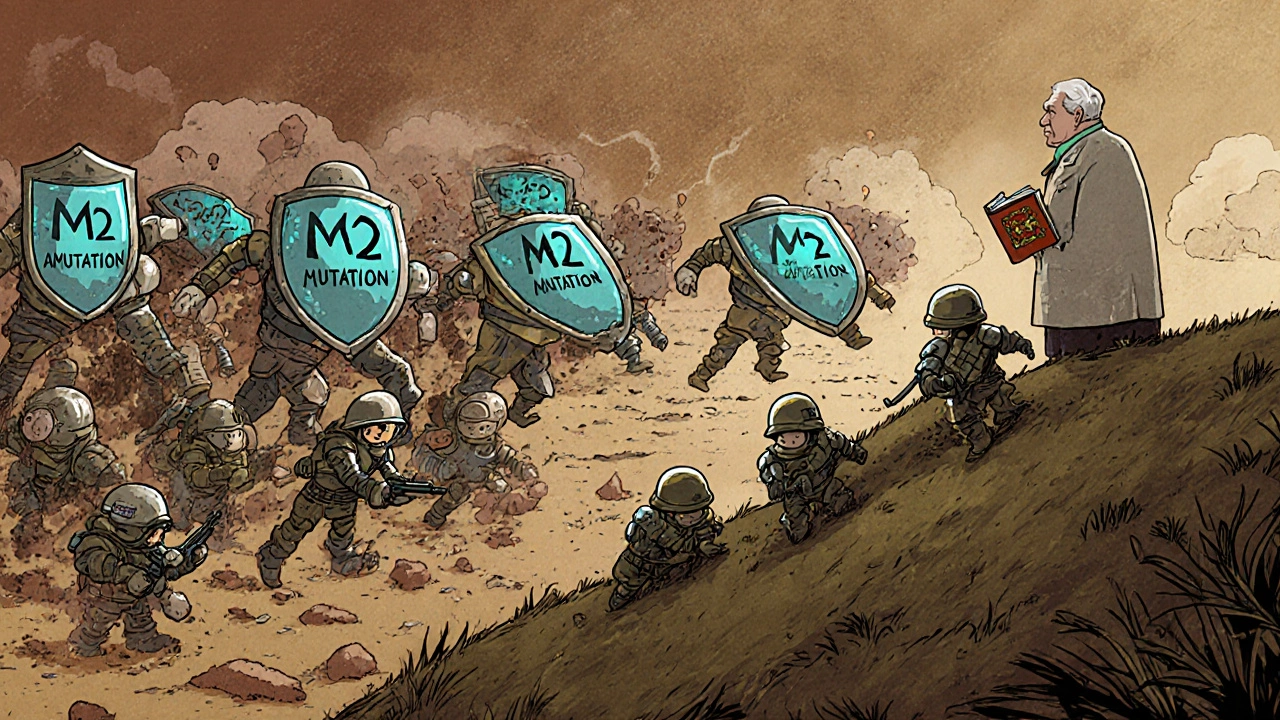

But here’s the catch: most strains of influenza A today are resistant to amantadine. A 2009 study from the CDC showed over 99% of circulating H3N2 and H1N1 strains carried mutations in the M2 gene that made the drug useless. These mutations changed the shape of the channel just enough so amantadine couldn’t bind anymore.

That’s why the CDC and WHO stopped recommending amantadine for flu treatment in the mid-2000s. Oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and zanamivir (Relenza) took over. They work differently-blocking neuraminidase, an enzyme the virus needs to escape infected cells and spread to others. These drugs still work against most flu strains today.

Still, amantadine hasn’t disappeared. It’s not a relic. It’s just been repurposed.

Amantadine and Parkinson’s Disease

In the 1970s, doctors noticed something odd. Patients taking amantadine for flu sometimes had less tremor and stiffness-even those who didn’t have the flu. That led to trials for Parkinson’s disease, and by 1975, the FDA approved amantadine for that use.

It doesn’t fix the brain’s dopamine shortage in Parkinson’s. Instead, it boosts dopamine release and blocks glutamate receptors, which can become overactive and cause muscle rigidity. For many patients, it reduces involuntary movements (dyskinesia) caused by long-term levodopa use. It’s not a cure, but it’s a useful tool in the toolbox.

Today, amantadine is still prescribed for Parkinson’s, especially in early stages or when dyskinesia becomes a problem. It’s often used alongside levodopa, not instead of it. Doses are lower than for flu-usually 100 mg once or twice a day. Side effects like lightheadedness, swelling in the legs, or confusion can happen, especially in older adults.

What About Other Viruses?

Scientists have looked at amantadine for other viruses too. Early studies explored its use against SARS-CoV-1 in 2003. Some lab tests showed it could interfere with viral replication, but no strong clinical evidence followed. The same goes for hepatitis C, HIV, and even some herpesviruses. In every case, the results were mixed or too weak to justify use.

One exception: amantadine has shown some effect against certain strains of influenza B in lab settings, but it’s not reliable enough for real-world use. Influenza B doesn’t even have an M2 channel like influenza A-it uses a different protein, so amantadine doesn’t work on it at all.

That’s why amantadine remains a narrow-spectrum antiviral. It only works on influenza A. And even then, only on the rare strains still sensitive to it.

Resistance and the Risk of Overuse

Amantadine’s downfall with flu came from overuse. In the 1990s, it was widely prescribed in Asia for flu prevention, especially during outbreaks. People took it without a prescription. It was cheap and easy to get. That created massive selective pressure on the virus. Mutants that could survive amantadine thrived-and spread.

Now, resistance is nearly universal. The same thing happened with antibiotics. When a drug is used too broadly, the bugs evolve around it. That’s why we don’t use amantadine for flu anymore. It’s a cautionary tale about how quickly viruses adapt.

Still, researchers haven’t given up on the M2 channel. Some new compounds are being designed to fit the mutated versions of the channel. If they succeed, we might see a next-generation version of amantadine in the future.

Who Still Takes Amantadine Today?

Today, if you’re prescribed amantadine, it’s almost certainly for Parkinson’s or a related movement disorder-not the flu. It’s also occasionally used off-label for chronic fatigue in multiple sclerosis patients, though evidence there is weak.

It’s not a first-line treatment for anything anymore. But it’s still in use because it works, safely, for a specific group of people. For Parkinson’s patients, it can mean the difference between being able to walk without shuffling or being stuck with stiff limbs all day.

And while it’s no longer a frontline antiviral, its history matters. Amantadine proved that viruses could be targeted with drugs. It opened the door for everything that came after-Tamiflu, Paxlovid, and even mRNA vaccines. It was the first real step toward treating viral infections with precision.

Side Effects and Warnings

Amantadine isn’t harmless. Common side effects include dry mouth, constipation, dizziness, and swelling in the ankles. In older adults, it can cause confusion or hallucinations. People with kidney problems need lower doses because the drug is cleared through the kidneys. Those with seizures or psychiatric conditions should avoid it.

It can also interact with other drugs like anticholinergics, certain antidepressants, and antihistamines. Always tell your doctor what else you’re taking.

It’s not something to take on your own. Even though it’s available as a generic, it’s still a prescription medication with real risks.

What’s Next for Amantadine?

Amantadine won’t be the next big antiviral. But it’s not dead either. Its legacy lives on in the science it inspired. Researchers are now studying how its structure can help design new drugs that target similar viral channels-maybe even ones we haven’t discovered yet.

For now, its role is small but steady: helping Parkinson’s patients move better, reminding us how quickly viruses adapt, and showing that sometimes the oldest drugs still have something to teach us.

Is amantadine still used to treat the flu?

No, amantadine is no longer recommended for treating or preventing influenza. Over 99% of circulating flu strains have developed resistance to it due to mutations in the M2 protein. Current guidelines from the CDC and WHO recommend oseltamivir (Tamiflu) or baloxavir instead.

Can amantadine help with Parkinson’s disease?

Yes, amantadine is still used to treat Parkinson’s disease, particularly to reduce involuntary movements (dyskinesia) caused by long-term levodopa use. It works by increasing dopamine release and blocking glutamate receptors in the brain, helping improve movement control. It’s often used alongside other Parkinson’s medications.

Why doesn’t amantadine work on influenza B?

Influenza B doesn’t have the M2 ion channel that amantadine blocks. That channel is unique to influenza A viruses. Since amantadine’s mechanism relies on binding to M2, it has no effect on influenza B, which uses a different protein structure for replication.

What are the main side effects of amantadine?

Common side effects include dry mouth, constipation, dizziness, swelling in the ankles, and sleep disturbances. In older adults or those with kidney issues, it can cause confusion, hallucinations, or low blood pressure. It’s important to monitor for these, especially with long-term use.

Is amantadine safe to take with other medications?

Amantadine can interact with several drugs, including anticholinergics, certain antidepressants (like SSRIs), antihistamines, and diuretics. These interactions can increase side effects like confusion or dizziness. Always consult a doctor or pharmacist before combining amantadine with other medications.

If you’re prescribed amantadine today, it’s likely for Parkinson’s-not the flu. Don’t assume it’s still a go-to for viral infections. Its role has changed, but its story remains important: a simple molecule that taught us how viruses work, how they evolve, and how we can fight back-with the right tools, at the right time.

Comments

Chris Dockter

Amantadine for flu? Lol. That’s like using a typewriter to write a novel. The virus laughed, mutated, and moved on. We’re still clinging to 60s tech while the world built AI. Pathetic.

October 30, 2025 at 13:58

Gordon Oluoch

The fact that anyone still considers amantadine relevant speaks to a systemic failure in medical education. Resistance wasn’t an accident-it was inevitable. Overprescription in Asia, no stewardship, no consequences. This isn’t science. It’s negligence dressed up as history.

October 31, 2025 at 23:35

Tyler Wolfe

I’ve got a buddy with Parkinson’s who swears by amantadine. He was shuffling before, now he walks like he’s 40 again. Doesn’t fix everything but it helps. Glad it’s still around for the folks who need it.

November 1, 2025 at 07:02

Andrea Gracis

wait so it doesnt work on flu anymore but still helps with parkinsons? that’s wild. i had no idea one drug could do two totally different things. so cool

November 3, 2025 at 01:57

Matthew Wilson Thorne

The M2 channel mechanism was elegant. Simple. Beautiful. A shame it got ruined by amateurs prescribing it like aspirin.

November 4, 2025 at 19:55

April Liu

I love how this post highlights that old drugs can still matter even when they’re not ‘trendy’ anymore. 💙 It’s like finding an old tool in the garage that still works perfectly for one specific job. Amantadine’s not dead-it’s just doing something quieter now.

November 5, 2025 at 07:48

Emily Gibson

It’s so important to remember that medical progress isn’t always about the shiny new thing. Sometimes it’s about knowing when to repurpose what you already have. Amantadine’s story is a quiet reminder that science doesn’t throw things away-it reuses them with wisdom.

November 7, 2025 at 03:41

Mirian Ramirez

i read this whole thing and i just wanna say thank you for writing it in a way that made sense to me. i’m not a doctor or a scientist but i’ve seen people i love struggle with parkinson’s and it’s so comforting to know there’s still something out there that helps, even if it’s old or not perfect. also i think the part about resistance is so important-we need to stop treating antibiotics and antivirals like they’re unlimited. we’re all gonna pay for it later. sorry for the typos lol

November 7, 2025 at 10:30

Kika Armata

You call this ‘quietly important’? This is a textbook case of scientific hubris. Amantadine was never a breakthrough-it was a lucky coincidence that got overhyped by underqualified clinicians. The fact that it still gets mentioned in the same breath as Tamiflu or Paxlovid reveals how little the medical establishment has evolved. The M2 channel was a dead end from day one. Real antiviral innovation requires structural biology, not blunt-force ion channel clogging. This post reads like a museum plaque for obsolete science.

November 8, 2025 at 05:18

Write a comment