Gallbladder Surgery: What It Is, Why It’s Done, and What to Expect

When your gallbladder, a small organ under the liver that stores bile to help digest fats. Also known as the biliary sac, it can become a source of serious pain and complications if blocked or inflamed. Your doctor may recommend gallbladder surgery, the removal of the gallbladder to treat gallstones, chronic inflammation, or infection. This procedure, called a cholecystectomy, the standard surgical treatment for gallbladder disease. is one of the most common operations in the U.S., with over 700,000 performed each year. Most people don’t miss their gallbladder after it’s gone—your liver keeps making bile, and your body adapts quickly.

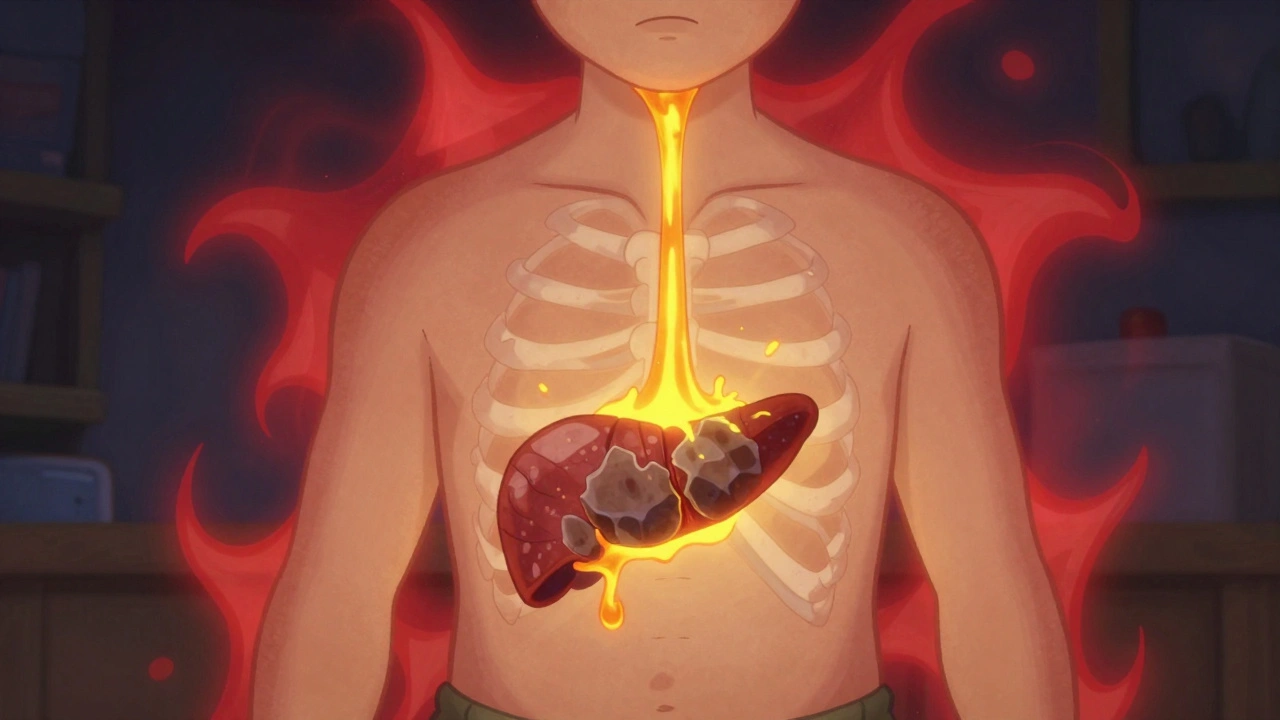

What triggers the need for this surgery? Usually, it’s gallstones, hard deposits that form in the gallbladder from cholesterol or bilirubin. These can block the bile ducts, causing sharp pain in the upper right abdomen, nausea, vomiting, and sometimes jaundice. If you’ve had repeated attacks, your doctor won’t wait. Left untreated, blocked ducts can lead to infection, pancreatitis, or even tissue death. Not everyone with gallstones needs surgery—some stay symptom-free—but if pain is frequent or severe, removing the gallbladder is the most reliable fix.

There are two main ways to do it: laparoscopic and open surgery. Laparoscopic is the norm—it uses tiny incisions, a camera, and special tools. Most people go home the same day. Open surgery, with a larger cut, is only used if there’s severe inflammation, scarring from past surgeries, or complications. Recovery is faster with the laparoscopic method—you’re usually back to light activity in a week and full routine in two to four weeks. You might feel bloated or gassy at first, and your bowel habits could change temporarily. Eating smaller, low-fat meals helps your body adjust as it learns to manage bile without the gallbladder.

Some people worry about long-term effects. Do you need to avoid all fats forever? No. Most people return to a normal diet after a few weeks. Others might notice more frequent bowel movements or diarrhea, especially after fatty meals. That’s usually mild and improves over time. Rarely, bile duct injury can happen during surgery, but it’s uncommon in experienced hands. If you’ve had symptoms for a while, delaying surgery often makes things worse—not better.

What you’ll find in the posts below isn’t just about the surgery itself. You’ll see how it connects to other health issues—like how gallbladder surgery can influence digestion patterns, how certain medications interact with bile flow, and why some people need follow-up tests for bile duct stones. You’ll also find practical advice on preparing for the procedure, what to ask your surgeon, and how to spot warning signs after you’re home. These aren’t theory-heavy articles—they’re real, usable tips from people who’ve been through it and professionals who manage the aftermath every day.

Gallstones cause painful biliary colic and can lead to dangerous cholecystitis. Learn how surgery - especially laparoscopic cholecystectomy - is the most effective long-term solution and when it’s the right choice.